This technical note accompanies

“‘Who invented the four modes of services supply?’”

“‘Plurilateral’ WTO services deal struck after breakthrough text released”

“If the EU and UK fall back on WTO commitments what does this mean for services?”

“India and South Africa pour cold water on alternative approach to WTO talks”

By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED DECEMBER 5, 2021 | UPDATED DECEMBER 5, 2021

WTO agreements contain two basic components. One is sets of general rules. The other is liberalising commitments that each country makes within those rules. Both components come from negotiations. The simplest way to understand the distinction is to start with trade in goods.

The WTO’s basic agreement on trade in goods is the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). This covers a range of general principles, including requiring countries to treat each other equally, plus exceptions and lots more. GATT has evolved to cover specific issues such as agriculture, product standards and subsidies, but those additional agreements are elaborations of the general rules.

Attached (or “annexed”) to GATT are each country’s commitments to lower tariffs and — nowadays — agricultural subsidies. These are the result of detailed negotiations and run to hundreds of pages for each WTO member.

The official term for the documents containing these commitments is “schedules”. They are essentially lists. But they also contain timetables for reducing tariffs and subsidies, which is why they are still called schedules even when commitments apply immediately, without a timetable, as is usually the case with services.

For example, as a result of decades of negotiations, the EU has agreed that its import duty on many types of shoes will be no more than 8%.

Multiply that by thousands of products and 164 WTO members and we get mountains of paper containing nothing but negotiated reductions in maximum tariffs (and agricultural subsidies).

Because these commitments are the result of negotiations, any amended or new schedules can be challenged according to agreed procedures. When all objections are dropped, they can be “certified” as the correct (unchallenged) documents.

In parallel, the WTO also has a General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). And its members have also attached lists or schedules of commitments. But the comparison with goods ends there. Services are much more complicated than goods. There are many types and each is treated differently — and that also applies to the schedules of commitments in services — whereas goods of all types can face the same main trade barrier: tariffs or import duty.

The WTO lists around 160 different types of services, grouped under 12 broad headings and sub-divided down to three levels:

- Business services (professional, computer, R&D, real estate, rental and leasing, etc)

- Communication services (postal, courier, telecommunications, audiovisual, etc)

- Construction and related engineering services

- Distribution services (commission agents, wholesale, retail, etc)

- Educational services

- Environmental services (sewage, refuse, sanitation, etc)

- Financial services (insurance, banking, etc)

- Health related and social services

- Tourism and travel related services (hotels, restaurants, travel agencies, tour operators, etc)

- Recreational, cultural and sporting services (entertainment, news, libraries and museums, sport, etc)

- Transport services (sea, inland waterways, air, space, rail, road, pipeline, cargo handling, etc)

- Other services

Each of these services can be delivered in four ways called “modes”:

- Mode 1. Cross-border supply. The supplier and customer are in different countries. The service is supplied across the border. For example a UK news agency supplying a news service to a newspaper in France

- Mode 2. Consumption abroad. The customer travels to another country and receives a service from a supplier in that country. For example a tourist staying at a hotel abroad

- Mode 3. Commercial presence. The supplier sets up business in the same country as its customers. For example a UK news agency setting up an office in France to supply French newspapers

- Mode 4. Presence or movement of natural persons. Workers or staff move to the customer’s country. For example, the UK news agency sends a British manager to France to run the office there. Note that this is not the same as “free movement of people”. Mode 4 may require visas and work permits, which could be fast-tracked or easier to obtain.

(Some economists are now talking about a fifth “mode”: the value of services incorporated in goods, but this is not yet formally in the WTO.)

None of this means “unfettered free trade” in services. Moreover, services regulation is a separate topic in the WTO — liberalisation and deregulation are not the same — although the distinction can be blurred, and an agreement among some members in 2021 adds streamlined regulation to the participants’ schedules of commitments.

GATS also allows countries to exclude “services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority”. These include utilities, social security and any other public service such as health or education that is not supplied commercially, does not have market conditions, or is not in competition with other suppliers. An annex on air transport completely excludes airline landing rights.

For example, the European Union’s schedule goes further in setting limits on commercial access to its government services and only opens up education services that are privately-funded.

And now it gets really complicated. Each WTO member’s services commitments are in several documents, each a maze of complexity. The EU’s schedules are used as examples here. They are particularly tough to understand.

WTO members’ commitments in services work in three ways:

- Market access — how much of the market is open to foreign service providers or customers, and where that is limited

- Non-discrimination (1) — equal treatment between foreign service providers and the country’s own suppliers or nationals, known as “national treatment”, and where that is limited

- Non-discrimination (2) — exemptions on treating other WTO member countries equally, known as “most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment”

The first two are in the main services schedule of commitments. These identify where the member’s market is open, or where it reserves the right to restrict access, or to keep the market totally closed.

The documents containing the commitments start with two originating from 1994, when the agreement setting up the WTO was signed, including the new agreement on services — or when the country joined the WTO after 1994:

- The main schedule (the EU’s is document GATS/SC/31 of 15 April 1994 — 97 pages). This is in two parts: “horizontal” commitments applying to all services sectors (to page 11), and commitments for the specific sectors (the remaining pages).

- Exemptions from non-discrimination (“MFN exemptions”) allowing the member to discriminate in certain cases (the EU’s is document GATS/EL/31 of 15 April 1994 — 13 pages).

Then come commitments as a result of negotiations after 1994, in financial services (1995, 1997), “mode 4” (movement of natural person, 1995), basic telecommunications services (1997) and domestic regulation (2021, schedules due to be certified in 2022 or later).

For the EU this is extra-complicated because services are generally handled by its member states and only partly by the EU as a whole. The EU’s main schedule and MFN exemptions are for the original 12 member states (EU–12). They still apply, except where the main schedule has been updated for financial and telecoms services, and “mode 4” by the subsequent negotiations.

The updates are in five documents plus three superseded. Seven of the eight are “commitments”; one is a list of “exemptions” from non-discrimination between other countries (“most-favoured nation” exemptions). Some include commitments for Austria, Finland and Sweden, which joined the EU in 1995:

- Financial services, supplement 1 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.1 of 28 July 1995 — 27 pages): replacing the original financial services commitments of the EU–12, Austria, Finland and Sweden

- Financial services, supplement 1, revision 1 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.1/Rev.1 of 4 October 1995 — 27 pages): again replacing the original financial services commitments of the EU–12, Austria, Finland and Sweden

- “Mode 4” (“movement of natural persons”), supplement 2 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.2 of 28 July 1995 — 20 pages): replacing the “mode 4” provisions in the original EU–12 commitment. These are the EU–12’s current “mode 4” commitments

- Telecommunications services, supplement 3 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.3 of 11 April 1997 — 10 pages): replacing the original telecoms commitments of the EU–12, Austria, Finland and Sweden. These are the EU–15’s current telecoms commitments

- Financial services, supplement 4 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.4 of 26 February 1998 — 24 pages): replacing supplement 1 revision 1

- Financial services, supplement 4, revision 1 (GATS/SC/31/Suppl.4/Rev.1 of 18 November 1999 — 19 pages): replacing supplement 4. These are the EU–15’s current financial services commitments

What about other EU member states? The only publicly available documents are those countries’ schedules from before they joined the EU. Post-Brexit UK has proposed its own schedule, but this has not been certified, so we can only see what the UK committed as part of the EU’s schedules.

There are a number of ways to find these documents for the EU or any other WTO member:

- In the WTO’s iTip database. This is the simplest way to find individual commitments. Here, although it is possible to search for the UK’s commitments, the results are for all the EU–12 (sometimes EU–15)

- Download the documents using these pre-configured searches, and selecting “European Union”

- Use the links above to download pdf versions (correct at the time of writing)

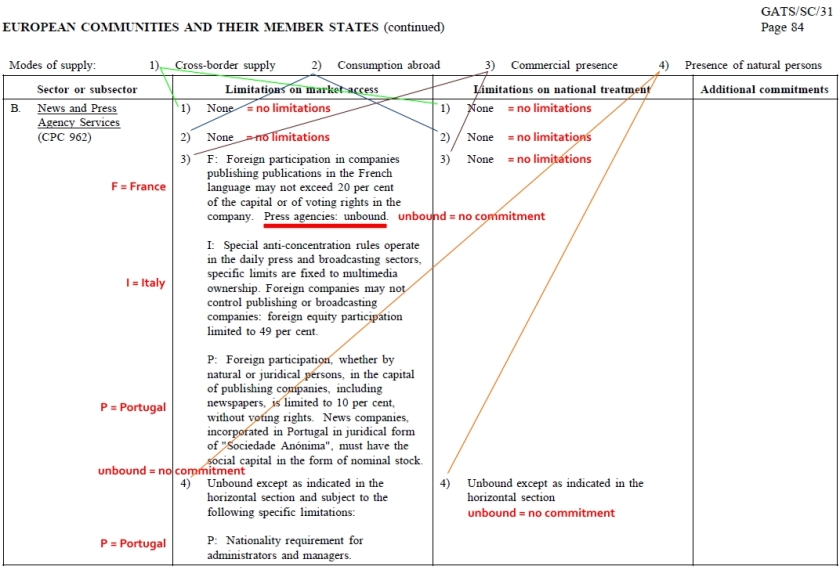

Looking inside the schedules is mind-boggling. Below is an example from the EU’s commitments. In the main schedules, where there are no limitations, the markets are open. Limitations are expressed negatively — the markets are open except where there are “limitations on market access” (column 2 in the example below). Where there are no commitments (“unbound”), the country is free to close the market.

The commitments also list “limitations on national treatment” (the first type of non-discrimination, in column 3 below). Again, where there are no limitations, the country will treat foreign companies as its own. Where there are limitations or no commitments at all (“unbound”), the country reserves the right to favour its own service providers.

Each of these is also specified for the four “modes” of supply, listed across the top of the page, with the limits on commitments running down the two central columns.

The EU’s main schedule document starts with “horizontal commitments” mainly dealing with limitations on investment, real estate ownership and “mode 4” (movement of professionals and other services workers or employees) across all services sectors.

Next come commitments in the 160 services sub-sectors — or more accurately, limitations on the commitments.

This is the section of the EU’s schedule on news and press agency services (chosen because it is one of the shorter items!):

For the second form of non-discrimination — most-favoured nation (MFN) — the exemptions are listed separately. They arise for a number of reasons, including preferential arrangements between countries that existed before the services were negotiated in the Uruguay Round.

This may explain why, for example, the EU reserves the right to discriminate in favour of Switzerland in a number of areas. The EU may be “grandfathering” sectoral deals with Switzerland that existed before 1994.

GATS and services issues in the WTO are explained here (introduction), here (FAQs), and here (more technical, pdf). The WTO also has a guide to reading services schedules.

Updates: None so far

Image credits:

Main image (montage of a services schedule) | Ibrahim Boran, Unsplash licence

Original WTO agreements in Marrakesh | the author