Rabbit hole noun

A complexly bizarre or difficult state or situation conceived of as a hole into which one falls or descends

— I wanted to show this woman descending into the rabbit hole: this loss of self, becoming a servant to her job and to the work — Jessica Chastain

Especially : One in which the pursuit of something (such as an answer or solution) leads to other questions, problems, or pursuits

— While trying to find the picture again on Google, I fell down the Cosmo rabbit hole, scrolling through a gallery of swimwear, then through “How to Be Sexier-Instantly” and then through all 23 slides of “Sexy Ideas for Long Hair.” — Edith Zimmerman

— Merriam Webster Dictionary online

By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED JUNE 8, 2021 | UPDATED JUNE 9, 2021

This is a cautionary tale about just how difficult it is to crack the secret codes of trade agreements. We can ask a simple question: how will the agreement change trade in a particular product. To reach the answer we often have to venture out into a wonderland of obscure paths and hidden traps.

Does it matter? Yes, if we want to find out for ourselves what is in the agreement. Bob Wolfe and I have argued at length about the need for more transparency in trade. This is true of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which is part of the rabbit warren. It is also true of free trade agreements.

Transparency doesn’t just mean making information available. It means making it accessible and understandable. Tracking down tariff commitments can be a nightmare, as this story shows.

A tale of four cheeses

On June 4, 2021, the UK reached a post-Brexit trade agreement with three countries in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA): Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. We can call them the EFTA3.

The deal is essentially an incomplete roll-over of the trading relationship Britain had with the three when it was in the European Union.

For example, an explanation on the EFTA website calls the chapter on services “state-of-the-art” among trade agreements. But it clarifies that the deal means service providers and investors will have access to each other’s markets under conditions that are “as close as possible to what they previously were under the internal market regime” of the EU and three EFTA countries.

There were also some tweaked improvements. The UK government website proclaimed:

“The agreement significantly cuts tariffs as high as 277% for exporters to Norway of West Country Farmhouse Cheddar, Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar, Traditional Welsh Caerphilly, and Yorkshire Wensleydale cheese.”

Those four cheeses have names that are protected as geographical indications in the UK and EU (and Iceland) and are considered to be high quality products. They will be protected in Norway too (and presumably Liechtenstein).

Too many of us are used to the British government over-selling trade agreements. When we saw that claim about the tariffs on cheese we wanted to know more.

But I was occupied with other things, and some journalists who might have followed up were busy with the G-7 finance ministers’ meeting.

Some people are tenacious. Jim Cornelius is one. How deep are those tariff cuts? Are the imports actually duty-free? Is this part of a quota? He kept digging on Twitter, and finally tweeted to me: “Why WTO on TRQ6?”

I had no idea. Why does Tariff-Rate Quota Number 6 among Norway’s commitments in the UK-EFTA3 agreement say “A WTO bound duty free quota member allocated to the UK of 299 tonnes under heading 0406”? (I think that should be “member-allocated”.)

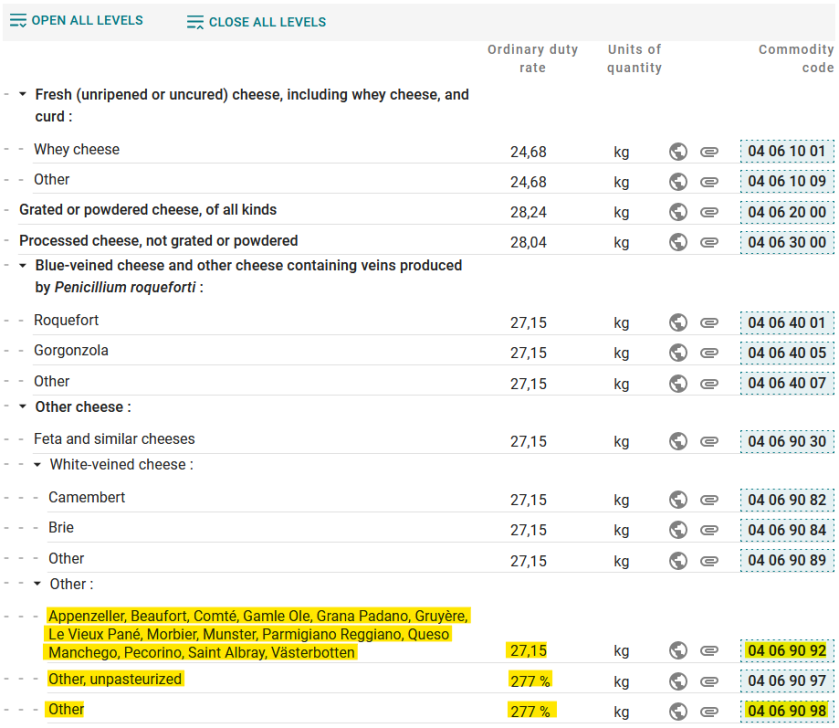

We know that “Heading 0406” is the customs code number for all cheeses and curds. Where do those four high-quality cheeses fit in?

I tried to find out. That took me on a truly bizarre journey. You could call it a rabbit hole, or a fiendishly difficult maze, or a series of obscure riddles, or all three.

I did reach the correct destination in the end, with a little help from a Norwegian official who urged me to “read the note carefully” and offered a few other cryptic tips. But not before I (and I think Jim too) had taken a number of wrong turns.

You don’t have to read all of this to find out what the real situation is. I’ll tell you now.

It turns out that the tariff reduction has nothing to do with a tariff quota — where imports inside the quota are duty-free, while quantities of cheese outside the quota are charged up to 277%. A duty of 277% would almost quadruple the price when the cheese lands outside the quota on Norwegian shores.

Instead, those four high-quality British cheeses are going to enjoy import duty of only 27.15 Norwegian kroner per kilogramme, which could be equivalent to perhaps about 25%, higher or lower depending on the price. That would be a lot less than 277%.

(Jim is still waiting for answers on the price of Yorkshire Wensleydale when exported to Norway. That might be difficult if the UK has never exported the cheese to Norway because of the 277% tariff — and no, I don’t know whether it ever has. See postscript below on how collaboration on Twitter produced part of the answer.)

Observe also that this “free trade agreement” is not entirely duty-free. Nor are many other trade deals.

So that’s the answer. Stop here if it’s all you want to know. Read on if you are interested in why this was difficult to find.

“Search” and other unhelpful short cuts

To begin with, it was difficult because Norway didn’t simply write in the agreement that imports of those four British cheeses will be charged NOK27.15/kg. Nor did it say where the tariff rate can be found. It just said they will now come under the customs product code 04069092.

I think of 04069092 as a prisoner’s number, erasing the individual’s personality, creating anonymity. Under the agreement, it’s the same prisoner, with the same unspoken name, but now a different number.

Numerical code numbers like this are convenient for customs departments and their officials. They can use them to find import duty rates and input any changes. The codes are also neatly devised so that the numbers are related. A few digits (like 0406) means a broad category (cheese). Adding more digits (04069092) sub-divides that category into narrower types of cheese (such as Yorkshire Wensleydale and others in Norway’s commitments). For customs officials it’s neat and logical.

For everyone else, even those of us working regularly on trade policy, it’s as easy to get lost as in a fog on the Yorkshire moors.

Part of the journey through the fog involved finding out Prisoner 04069092’s real name and how he or she is treated. But I’m jumping ahead a bit. (And the number is for a group of prisoners, not one, but you get the picture.)

The British government is happy to announce a successful trade negotiation with a news story or press release, but is usually slow to publish the text. The Norwegian government published a text in Norwegian and English almost immediately.

(The EFTA website has also published the rules part of the agreement, without the market access commitments on tariffs, along with a summary.)

The Norwegian text is about 1,620 pages. Jim and I were trying to find out one small piece of information — what the import duty is on those four British cheeses. Surely, the quickest way is to search the document for “cheese” and “Wensleydale” and even “TRQ” (for tariff-rate quota). That’s what I did.

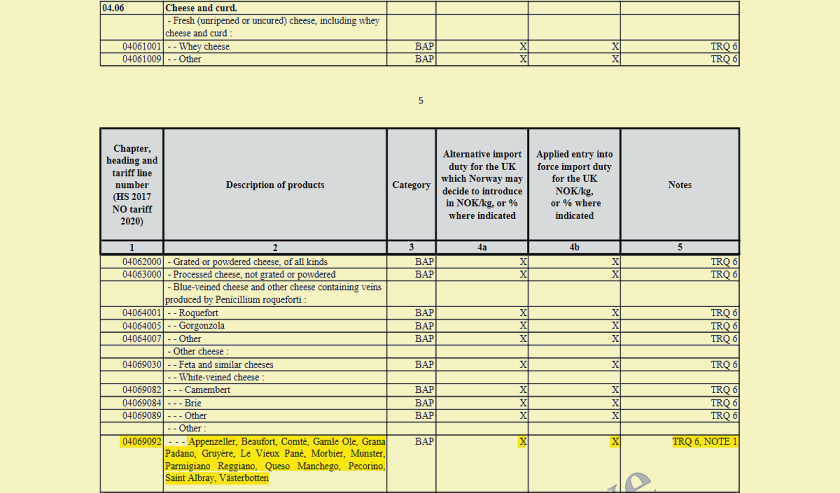

Searching for “cheese” first produced 14 prisoner numbers from 04061001 to 04069098. No Wensleydale. No Cheddar. No Caerphilly. There weren’t even any tariff rates. Just Xs for the import duty used, and for an “alternative” (whatever that means).

Scrolling back through several pages to the top of the table reveals that “X” means “no concession” — trade jargon for no tariff reduction.

In the notes column they all had “TRQ6”. Prisoner 04069092 also had “NOTE 1” alongside “TRQ6”. But I hadn’t been introduced to 04069092 yet, so I didn’t know it was significant. Under “description of products” there were some names from continental Europe, but none from Britain.

And this is where I took a wrong turn, because in fact this is where part of the answer lies. I had found it, couldn’t see it (could you?), and headed off in the wrong direction.

The next obvious search is for “Wensleydale”. I found it. Bingo! I thought. Wrong.

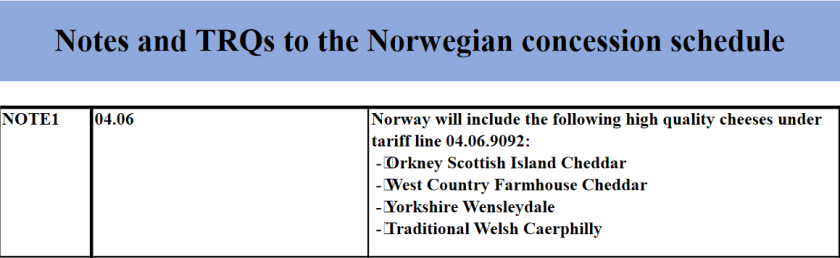

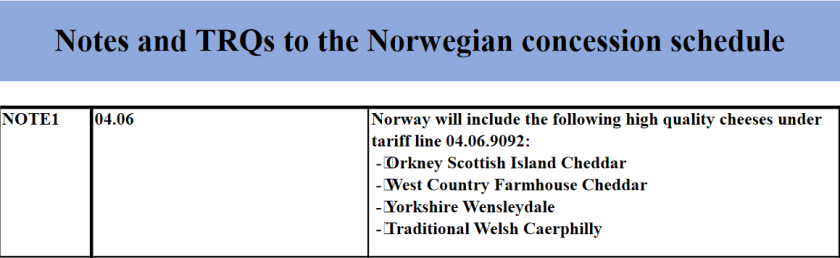

The first result came in a table headed “Notes and TRQs to the Norwegian concession schedule”. And Note 1 is about Prisoner Family 04.06 (which is cheese and curd) and says Norway will include the four cheeses under tariff line 04.06.9092. Take away the points and we have Prisoner 04069092. And there are the four British cheeses. Boy, am I pleased to meet you, Prisoner 04069092!

The next result showed that “Yorkshire Wensleydale” is among British names that are going to be recognised as protected geographical indications in Norway. This is about the use of the name (intellectual property), not the tariff, so we can ignore it. A couple more results seem to be about the prisoner numbers the UK gives to Wensleydale, so also irrelevant.

In other words, the sole reference to Wensleydale that is about tariffs, in the whole 1,620-page document, is in that table.

Further down the table is a description of TRQ6 (tariff-rate quota number 6) which is also for Prisoner Family 04.06:

“TRQ6 — 04.06 — Cheese and curd. A WTO bound duty free quota member allocated to the UK of 299 tonnes under heading 0406.”

Jim found it first, and asked me “why WTO?” I jumped to two conclusions, one right, one wrong.

The right one was that this refers to a tariff quota — duty-free inside the quota — that Norway had legally “bound” (committed) in the WTO.

The wrong one was that this explains the British government’s claim about steep cuts in tariffs.

The WTO maze

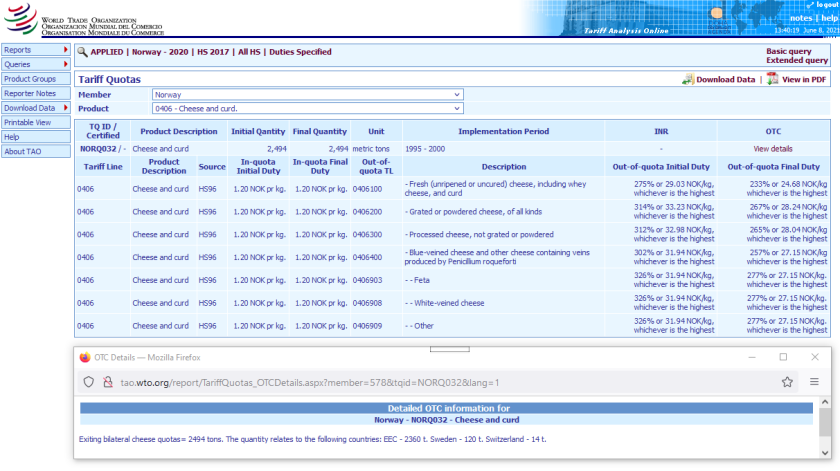

So the next place to turn to was the WTO. What commitments has Norway made in the WTO on tariffs and tariff-quotas for cheese? The WTO’s information is extensive and sophisticated. But extensive and sophisticated is the opposite of what we need.

We just want to see the document that spells out Norway’s latest commitment on cheese. There are at least two databases offering the answer.

One contains all Norway’s commitments on opening its market to fellow-members. This goes all the way back to before the WTO was born in 1995 (previously it was the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade, GATT).

It includes Norway’s initial WTO commitments from 1994 on tariffs and tariff quotas on thousands of products. Then come a series of updates, because, well, things change, including those customs code numbers. In the database, all we can see is the documents’ titles. Which one has the latest commitment on the cheese tariff quota? Impossible to tell.

To cut a long story short, it’s part 2 of WTO document WT/Let/1505, which only contains this tariff quota, nothing else. But you have to find it and then open it to see.

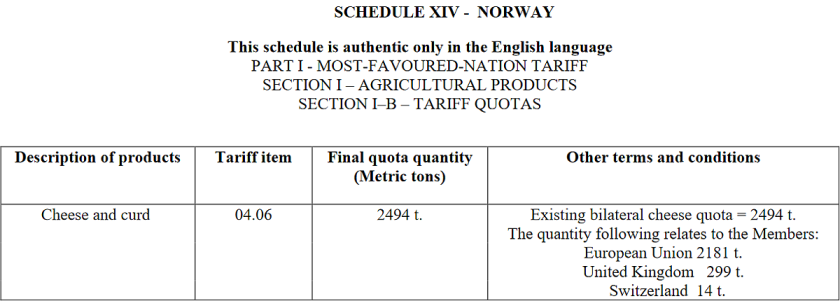

Here, Norway has changed its original commitment in the WTO. In this tariff-quota it originally allowed cheese (04.06) from the EU and Switzerland to be imported duty-free for up to 2,494 tonnes. Now that Britain has left the EU, the original EU share of 2,480 tonnes is split 2,191 tonnes for the EU27 and 299 tonnes for the UK.

I jumped to the conclusion that the British government’s claim about those four high-quality cheeses came from this. They would enjoy duty-free access under the small tariff quota. But I was wrong. This tariff quota is for all types of cheese. The claim was about something else.

In any case I still hadn’t found what the out-of-quota tariff is, only the quota size. So I had to hunt for another document. Should it be the latest revision? Or an earlier one? No. They do not contain the tariffs, only the tariff quotas.

Eventually I tracked down this: Norway’s original WTO commitments from 1994, where some parts no longer apply because they have been updated, but the tariffs haven’t changed:

Prisoner 04069092 is not listed, but under the coding system it could be part of 04069000 (“other cheese”). The tariff quota is not in any of the updated documents either, so the original 1994 commitments also still apply. To see them, we have to click on another tab in the Excel file. The 120 tonnes for Sweden was merged with EU’s when Sweden joined in 1995 to make a quota of 2,480 tonnes:

This was confirmed in another WTO database, Tariff Analysis Online.

Still no sign of Prisoner 04069092. The “tariff line” (the official name for products identified by those code numbers) does not exist in Norway’s worldwide commitments in the WTO.

It seems to exist only in two of Norway’s free trade agreements.

Prisoner 04069092, whose names were only those of EU cheeses, was originally captured by an agreement between the EU and Norway (presumably the European Economic Area agreement). Prisoner 04069092 is now also captured by the UK-EFTA3 agreement, with the four names of UK cheeses added.

I surrender

Presumably somewhere in some document is the additional clarification that Norway’s imports for Prisoner 04069092 will not be charged the “whatever is higher” part of the duty bound in the WTO. It will be charged NOK27.15/kg instead, which is currently lower.

Where is that written? I’ve given up hunting. I’ll just take Simen Svenheim’s word for it:

“It will move from tariff line 04.06.9098 to 04.06.9092. Norway moved from a specific tariff on cheese (kr 27.15) to ad valorem (277%) a few years back but retained the specific tariff for some cheeses. These four cheeses will be added to that list.”

I wasn’t feeling very clever when I started. After all those wrong turns, I now feel completely stupid.

I have just two concluding observations. As far as I can see:

First, judging by the link Simen provided, to data from Norwegian Customs, the NOK27.15 duty is an “applied” rate. That’s fine if it is below the legally committed ceiling known as the “bound” rate.

And yes, 04.06.9098 is charged 277%, whereas for 04.06.9092 and several other types of cheese the duty is NOK27.15/kg (or a bit more), which could be around 25% at current prices.

Second, unless there is a commitment written into an agreement somewhere — which we haven’t seen yet — there’s nothing legally to stop Norway reverting to 277%.

But by then Norwegians might be so addicted to Yorkshire Wensleydale that they would riot in the streets of Oslo and Bergen if the price shot up again.

Then again, they might not.

Postscript: Collaboration yields more information

Following Jim Cornelius’s lead, several other people on Twitter tried to find out what this would really mean for those four high-quality British cheeses.

One who took up the baton was Sam Wilkin (@CellarmanSam), Head Cheesemonger at The Cheese Bar (@thecheesebarldn) in London.

He tweeted, confirming that the new tariff fixed at NOK27.15/kg is considerably lower as a percentage of the higher prices of artisan cheese:

“So I had a chat with Neal’s Yard Dairy — they currently export a tiny amount. They are limited to a 2-tonne quota, above which they have had to pay 277% making it unviable. The new flat rate [NOK27.15/kg] benefits higher value artisan products as it is a smaller fraction of the price.

“For bulk commodity items it is less positive as a flat rate could equal a 100% tariff versus let’s say the equivalent of a 25% on a higher cost quality item. NYD see this as a real opportunity, Norway is a wealthy country with a healthy appetite for cheese.”

Updates: June 9, 2021 — adding the postscript and Sam Wilkin’s tweets

Image credits:

• Featured image collage. Wensleydale cheese | Wikimedia, public domain. Alice and hare | Pixabay, CCO. Alice and tea party | John Tenniel, public domain

• A traditional field barn near Sedbusk, Wensleydale | Andrew, Flickr, CC BY 2.0