By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED MAY 5, 2018 | FIRST PUBLISHED ON UK TRADE FORUM APRIL 3, 2018 | UPDATED JULY 11, 2023

Among the thousands of policy questions facing Britain after it leaves the EU is what its approach should be for geographical indications.

These are names — like Melton Mowbray pork pies, Rutland bitter and Bordeaux wine — that are used to identify certain products.

The UK’s policy will affect both its own and other countries’ names, and it has now taken first steps in revealing what its approach will be.

People’s views of geographical indications range from cherishing them as precious cultural heritage and commercial property, to annoyance and scorn.

What are they? And what are the decisions facing the UK? This is an attempt to explain them simply. It’s in two main parts with a small third part tacked on.

Part 1 is the basics. Part 2 (below) looks beyond that at policy.

Meanwhile the waitress above mentions 10 types of food and drink. How many are geographical indications? The answer is in Part 3 at the end.

More details can be found on the websites of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and World Trade Organization (WTO).

Continue reading or use these links to jump down the page

PART 1 BASICS

What are geographical indications (GIs)? | What do they apply to? | Are they always place names? | How do they relate to rules of origin? | Why protect them? | What does protection mean? | How much protection?

PART 2 POLICY

How are geographical indications protected? | What does the UK face with the EU? | What do we know about the UK’s plans? | What does the UK face with other countries? | What does the UK face in the WTO? | Some GI titbits — style/method, orange, champagne, gruyère, feta

PART 3 WHAT THE WAITRESS SAID

PART 1 BASICS

What are geographical indications (GIs)?

They are names used to define both the origin and the quality, characteristics or reputation of products.

Origin is not enough. A cheese made around Roquefort-sur-Soulzon in southern France cannot be called Roquefort unless it is blue, made from sheep’s milk and meets a number of other criteria.

What do they apply to?

The vast majority of geographical indications are on food and drink, particularly wines and spirits. This is because soil and climate conditions can contribute to the products’ specific qualities.

Geographical indications are names. Protection only restricts the use of the name. It doesn’t prevent copying or imitation.

Some countries protect other types of products as well. For example in the UK “Native Shetland Wool” (agricultural but not food, although bizarrely it appears in the UK’s register of “foods”), “Swiss” watches (non-agricultural) in Switzerland, and some types of carpets and other handicrafts around the world.

Thailand would even like a service to be protected — traditional Thai massage — but internationally geographical indications are only used with goods.

Are they always place names?

Usually the terms used are place names, but sometimes they are other words associated with specific regions.

For example basmati is a long-grain fragrant rice variety and not a geographical name. However, it is associated with the Punjab regions of India and Pakistan, although its status as a geographical indication is debated (the EU doesn’t recognise it) because it is grown elsewhere too.

How do they relate to rules of origin?

This has absolutely nothing to do with rules of origin, which are about customs procedures — determining whether a product can be called “made in” a certain country and therefore should qualify for duty-free trade or other special treatment under trade agreements.

Geographical indications are a type of intellectual property, a form of “branding”, along with copyright, trademarks and others, because the products’ characteristics are the result of production techniques as well as location.

Why protect them?

Protection is intended to benefit both consumers and producers. The EU speaks of ensuring a product is “authentic” (for consumers), and providing a marketing tool to give producers “legal protection against imitation or misuse of the product name”.

Under WTO rules, the objective is to avoid misleading the public and unfair competition.

What does protection mean?

It’s important to understand this. Geographical indications are names, so protecting them means that what’s restricted is only the use of the name. It doesn’t prevent copying or imitation — that’s handled by copyright and patenting.

“Feta” is protected in the EU, meaning the name can only be used in the EU if the cheese is made in Greece. Nevertheless, an identical or similar cheese made in the US (where it’s not protected) can be sold in the EU. It just can’t be called “feta”.

How much protection?

The bottom line for the WTO’s 164 members (including the EU and UK) is what is required in its intellectual property agreement (known as TRIPS or Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights). The agreement only sets minimum standards. It does not deal with individual names. How countries meet the standards and which names they protect is left up to them through their different legal systems.

The section on geographical indications is short. It has three parts, Articles 22, 23 and 24:

- In general (Article 22), countries have to protect geographical indications to avoid misleading the public and avoid unfair competition. By this criterion, “Californian champagne” should be fine since consumers would be clear that this did not come from the Champagne region of France. But …

- For wines and spirits (Article 23), protection is taken to a higher level — even if there is no danger of misleading the public or creating unfair competition. So “Californian champagne” is no longer valid. Except that …

- There are a number of exceptions (in Article 24). These include if a term has become generic — cheddar cheese is clearly one case since it’s been made around the world for decades, if not longer. Also an exception is when the name was registered as a trademark before the WTO’s agreement was negotiated (“grandfathering”) — Parma ham has long been a trademark in Canada, an irritant for Italians who were unable to sell Prosciutto di Parma there until recently. The EU has waged a long-running and still unresolved battle with the US over the use of “Champagne”.

When the EU negotiates for its geographical indications to be protected in other countries, part of the effort is about reclaiming names that have become generic — or more vividly to “clawback” names that have been “usurped”. Feta cheese is one case. This 73-page document is what the EU and US have agreed for wines.

PART 2 POLICY

How are geographical indications protected?

The names are usually the property of groups of producers or regional or national authorities, not individual companies.

How they are protected depends on where, and this matters for the UK’s future relationships, such as how it seeks to have its own names protected abroad.

The European Union probably has the most detailed and sophisticated system.

Its database of all protected names is called GI View. Each name is identified by whether it is protected by registration according to criteria (including “applied” for, “published”, or “registered”) or under a trade agreement. (Details in this technical note. The UK has its own database.)

For registered products, stricter criteria apply to “protected designation of origin (PDO)” and only some products are eligible. A wider category is “protected geographical indications (PGI)”.

A third, “traditional speciality guaranteed (TSG)”, emphasises the production method and is not for geographical indications although the EU includes it as a quality label alongside geographical indications. The EU says this is “without being linked to a specific geographical area” although names are associated with individual countries and some of the 65 products currently listed contain geographical references. For example the TSG “traditionally reared pedigree Welsh pork” sounds Welsh although the specification does not rule out the breed being farmed elsewhere provided the conditions are the same.

The EU’s database contains names of almost 3,000 wines, over 1,600 from the EU (some registrations still being considered). Only six are British.

For spirits there are 255 EU geographical indications including some whose protection is being considered — 260 if aromatised wines are included, such as some glühwien and vermut. Around 150 are non-EU. Two are British: Scotch whisky and Somerset cider brandy. Part-British are Irish whiskey, cream and poteen, made anywhere on the island of Ireland.

For other products, there are over 1,800 “registered”, “published” or “applied for” geographical indications from both EU and non-EU countries (excluding traditional specialities or TSGs); 75 are British.

(See also this official UK list of names. Among the foods the UK wants to protect as a TSG is “watercress”.)

At the other extreme used to be Norway. A few years ago, WTO members were asked to fill in a questionnaire with some examples of geographical indications they protected. Norway said it couldn’t be sure because it used consumer protection law rather than a register of names, meaning a term would have to be in a court case to know for certain.

It managed only one possibility. “‘Hardanger’ might be a protected name,” it suggested (page 80 here). Since then, Norway has brought its system much closer to the EU’s, and updated its replies to the WTO questionnaire.

Some countries use specific geographical indications laws and registers. Some use consumer protection. In the US and many others protection is by trademarks and certification marks. There are even variations of approach within the EU. The UK told the WTO that it uses common law (“tort of passing off”) for some terms and trademark law for others, although fundamentally the UK is applying EU law. (See the annex in this now out-of-date WTO document.)

Because the EU attaches so much importance to geographical indications, one of the key questions about the UK-EU relationship after Brexit is what happens to EU names currently protected in the UK? British producers will also want to know whether their products’ names will still be protected in the EU–27.

What does the UK face with the EU?

![]()

THE EU’S POSITION

● The full EU position paper from September 2017

● The draft Withdrawal Agreement, February 2018, see the heading “Intellectual property: continued protection in the United Kingdom of registered or granted rights”

● The March 2018 version with parts agreed highlighted in green. On intellectual property, the section on geographical indications was not highlighted as agreed, but those on trademarks and plant varieties were

● The November 2018 agreed draft confirming that the UK will continue to protect EU names

In theory, when the UK leaves the EU it will be free to decide how it protects geographical indications and which names to protect, so long as it complies with the WTO principles.

Will the UK move away from the EU’s near-obsession with geographical indications? It might not have too many wines, but it does have Scotch whisky and a lot of food products.

Its hand might also be forced by its future relationship with the EU. Geographical indications have always been a priority for the EU in its free trade negotiations and the EU quickly demanded protection to continue in the UK after Brexit, at least for products whose names are already protected in the UK.

This is likely to mean the UK setting up its own lists of protected geographical indications with associated legislation.

What do we know about the UK’s plans?

(Update: Since this was written, part of the picture has become clearer, not least because the 2019 version of the Withdrawal Agreement was agreed. See this newer piece on the implications for EU names in the UK, UK names in the EU, and more.

Then on October 13, 2020, the UK government published a new guide, “Protecting food and drink names from 1 January 2021”. The coverage, complete with the three types of protection — Protected Designation of Origin (PDO); Protected Geographical Indication (PGI); Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG) and their own logos — indicates that the UK system will indeed closely mirror the EU’s system.

Finally, the UK-EU post-Brexit trade deal, agreed on December 24, 2020, confirms that the Withdrawal Agreement applies. It also leaves open the possibility of future talks. See this.)

It’s taken some time — from the November 14, 2018 proposed Withdrawal Agreement tentatively agreed in Brussels, the July 2018 UK policy paper, and Britain’s “no deal” paper on geographical indications (now replaced by this), and finally the 2019 Withdrawal Agreement and 2020 post-Brexit deal.

We now know that UK names currently protected in the EU, and EU names currently protected in the UK should both continue to be protected in Britain, assuming the deal holds. But there’s more.

![]()

WHAT THE UK WHITE PAPER SAYS …

38. Included in the remit of wider food policy rules are the specific protections given to some agri-food products, such as Geographical Indications (GIs). GIs recognise the heritage and provenance of products which have a strong traditional or cultural connection to a particular place. They provide registered products with legal protection against imitation, and protect consumers from being misled about the quality or geographical origin of goods. Significant GI-protected products from the UK include Scotch whisky, Scottish farmed salmon, and Welsh beef and lamb.

39. The UK will be establishing its own GI scheme after exit, consistent with the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS). This new UK framework will go beyond the requirements of TRIPS, and will provide a clear and simple set of rules on GIs, and continuous protection for UK GIs in the UK. The scheme will be open to new applications, from both UK and non-UK applicants, from the day it enters into force.

… AND THE “NO DEAL” PAPER

When we leave the EU we will set up our own GI schemes which will be WTO TRIPS compliant, broadly mirror the current EU regime and be no more burdensome to producers. Details to be explored in a public consultation include the UK GI logo and appeals process. The protections will be similar to those enjoyed now by UK GI producers, with all 86 UK GIs given new UK GI status automatically. The UK would no longer be required to recognise EU GI status. EU producers would be able to apply for UK GI status. We will be publishing guidance on the UK GI schemes in early 2019.

Various UK papers released in 2018 showed that Britain would set up its own system that would “broadly mirror” the EU’s (see box).

It was not until the November 14, 2018 draft Withdrawal Agreement (confirmed in the 2019 final text) that the situation for the thousands of names from EU–27 countries was clarified. It said any names protected in the EU at the end of the Brexit transition period would be registered in the UK with the same level of protection as they now enjoy, without any re-examination (see pages 87–89 of the text).

What would have happened without the Withdrawal Agreement is unknown but now moot. (At the time, it caused concern in Brussels where officials were reported to be studying whether the UK might risk violating the WTO’s “national treatment” principle — the UK might be discriminating against the EU and others if it automatically continued to protect its own names, while requiring other countries’ names to go through a registration process.)

By following the EU system, the UK has extend the higher level of protection beyond wines and spirits to foods such as Cornish pasties and Melton Mowbray pies.

How the British system might be changed in the future is unclear. Some speculated that the UK was aiming for a weaker system, allowing it to strike trade deals more easily with countries that are more sceptical about geographical indications, such as the US, Australia, New Zealand and Canada (more below). (See this Twitter thread by former trade official David Henig, also below, and this tweet by former trade minister Greg Hands, also below.)

There was also speculation that because Britain might use geographical indications as a bargaining chip to extract a better post-transition deal from the EU. (See this Politico report and my own tweets here and below.) There’s no evidence that the UK did that.

What does the UK face with other countries?

Beyond the EU, the world of geographical indications has sometimes been described as a divide between old world countries, with traditional methods and products they want to protect, and the new world whose immigrant populations brought those techniques with them. It’s a bit more complicated than that. For example Taiwan is in the so-called new world group and some US producers now want protection for their own products, from wines to Idaho potatoes. But there is some truth in it.

In negotiations with some countries such as other Europeans, India and so on, the UK will be under pressure to protect their names. With others such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the US and some Latin American countries, the UK may be the one making the most demands to protect its names.

If it continues to protect EU geographical indications, Britain may need to tread carefully with the GI-sceptical “Anglosphere” countries. For example in its free trade talks, the UK might be under pressure to allow imports of Australian feta cheese (and it might want to make its own too).

But for now the UK is obliged to protect all names protected by registration in the EU but not those protected in the EU via bilateral agreements. (The obligation comes from the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement and UK-EU post-Brexit deal.)

The EU has deals on geographical indications with other countries, either as part of free trade agreements or separately.

With Brexit, the UK has rolled the EU’s free trade agreements over into its own. Some of these continuity deals include geographical indications (such as with Japan, Switzerland and Vietnam); some don’t.

The UK has also signed continuity agreements specifically on geographical indications, particularly for wines and spirits, including with the US and Australia. (See details in this technical note.)

What does the UK face in the WTO?

The WTO agreements signed in 1994 included a commitment to set up a multilateral register for geographical indications of wines and spirts. Almost a quarter of a century later, members still have not agreed on how to do this.

The EU and its allies want the register to have some legal effect: if a name is on the register, then that should have some legal implications in all WTO members. The US and its allies prefer a register that is little more than a database of information, which countries would be free take into account (or to ignore) when they decide whether to protect a particular name.

In December 2019, the talks’ chair issued another forlorn report on how the talks have not progressed. He contrasted this with activity in geographical indications in bilateral and regional talks and elsewhere outside the WTO.

A second issue is whether to give some or all other products the same higher level of protection as is now given to wines and spirits (Article 23), and presumably to include them in the multilateral register. This is often called “extension”: extending the higher-level protection beyond wines and spirits.

Although this has been discussed at length in the WTO, members still have not even agreed whether it is officially a negotiation. A large number of countries support the move, but in some cases for complex bargaining reasons. The US, Australia and so on oppose it on the grounds that it would be too burdensome and restrictive, and that the standard level (Article 22) is good enough.

The UK will have to decide how to approach these questions, and also the WIPO treaties on geographical indications.

Some GI titbits

Geographical indications are complicated. Every argument has a counter-argument so they are a perfect playground for intellectual property lawyers, as the endless and bottomless debates in the WTO show. Here are some illustrations.

“-style”? Or “-method”?

If “Bulgarian yoghurt” can only be made in Bulgaria, what about “Bulgarian-style” yoghurt? One view is that this is a useful indication of what the product is, helping rather than confusing consumers.

Against that is the argument that “Bulgarian-style” has no owner and no definition. The term could be abused. The reputation of yoghurt associated with “Bulgaria” would be damaged, hurting both consumers and genuine Bulgarian producers. The poor reputation of parmesan cheese made outside Italy is a real-life example.

After all, one of the features of geographical indications is that they have owners responsible for maintaining the quality and reputation. The loose term “Bulgarian-style” would not have that.

Orange: homonyms and more

Several places could have the same name, or names that sound the same (homonyms). The WTO agreement broadly covers that, but homonyms can still get pretty complicated. In late 2000 Australia entertained WTO delegates with an analysis of “Orange”. It’s a place name on five continents, some with vineyards producing what could be called “Orange wine”. And then there’s wine made from oranges. Orange is also a colour and a phone company’s trademark. It’s linked to words in other languages, including Persian where the fruit is named after Portugal, and so on. (See page 6 of this.)

Champagne: Swiss and Indian

A small village in northern Switzerland is called Champagne. It used to produce a still white wine with the name, but not since 2005. Pressure from France put an end to that. Meanwhile, in the WTO debate on “extension”, a US delegate once remarked wryly that Darjeeling tea, a claimed geographical indication, is advertised as “the champagne of teas”.

Gruyère

Gruyère is a region in Switzerland surrounding the medieval village of the same name (actually Gruyères with an “s”). The cheese was first made there in 1115. It’s now been produced elsewhere for generations and the name has become generic, sometimes using “Gruyère” or an equivalent in another language.

Gruyère is not in France. Nevertheless, France has managed to register “French Gruyère” produced in a dozen departments as a protected geographical indication in the EU. Despite the stereotype of Swiss cheese, authentic Gruyère has no holes. But the French version does: it “must have holes ranging in size from that of a pea to a cherry”, according to the EU regulation.

In Switzerland, “Le Gruyère” now has a Swiss protected appellation of origin (AOP) covering four whole cantons and parts of a fifth.

But is it protected in the EU? Not by registration. The EU’s GI View database shows Gruyère protected under a 2014 agreement with Switzerland. (All but two of the 188 Swiss names are protected this way. The two exceptions are being applied for through registration, but the applications are made jointly by Austria, Germany and Switzerland for fruit spirits produced around Bodensee/Lake Constance.)

As an illustration of how complicated these names can be, Switzerland and Greece also promise not to translate “graviera” (γραβιέρα) as “gruyère” and vice versa.

Because Gruyère is not protected in the EU by registration, but through the bilateral agreement, the UK was not obliged to continue to protect the name after Brexit. But all the Swiss names in the agreement with the EU have been copied into the UK-Switzerland agreement. So Gruyère stays protected in Britain.

On a much smaller scale than the EU, Switzerland has also been trying to “reclaim” terms that have become generic elsewhere. In 2013 it secured US registration for “Le Gruyère” as a certification mark (similar to trademark). But a joint application* by French and Swiss producers to protect just the word “Gruyère” in the US has been challenged and remains unsettled — a federal judge has ruled it cannot be protected but the ruling is being appealed. (More gory detail is here.)

* alternatively, search here for serial/registration number 86759759

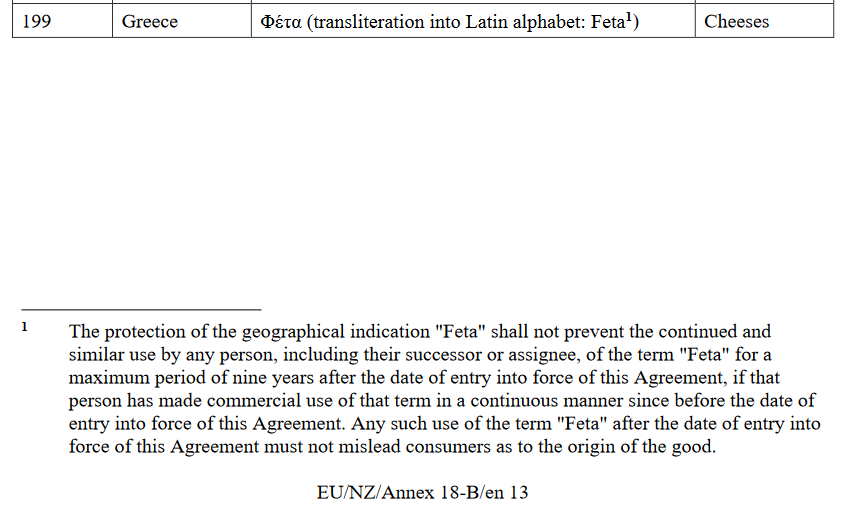

Feta

This is one of the most-debated names in the WTO. The minutes of this meeting contain 14 pages of debate in which “feta” appears 50 times. Similarly for these meetings. Is it eligible for protection? Is it generic? Where exactly is its origin? Greece, Bulgaria, Denmark even? Is the legal situation in the EU contradictory? Should migrants to Australia be allowed to continue to use the name for the cheese that their ancestors made? Is feta actually produced in Australia by immigrants or by large companies?

One “new world” producer has succumbed. In 2023, New Zealand agreed to protect the name feta for the Greek cheese.

EU-New Zealand free trade agreement Annex 18

Still have an appetite?

In 2005, the WTO Secretariat summarised the debates on “extension” in the organisation in a 44-page 21,000-word paper. Heavy going but essential reading for anyone wanting to dig deep into the subject. You can also download this 232-page guide from the International Trade Centre. Either way, keep a good Irish whiskey or Spišská borovička at hand.

FINALLY PART 3 WHAT THE WAITRESS SAID

At the top of this article, the waitress refers to 10 types of food and drink (not counting the general “lamb” and “cheese”). Some are geographical indications, some are not:

Geographical indications protected in the EU and therefore the UK — Cornish pasty; Tiroler Bergkäse; Caerphilly; French Gruyère; Amarone della Valpolicella; Armagnac. The EU has agreed to protect Le Gruyère from Switzerland but this does not (yet) appear in the EU’s database.

Names that are generic in the EU/UK — Cheddar (except “West Country Farmhouse Cheddar cheese,” which does include the original Cheddar area in Somerset, and “Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar”, from over 1,000 km away)

Not geographical indications in the EU/UK — New Zealand lamb (although “Scotch lamb” is); Evian (Evian is a place, a lakeside French town at the foot of the Alps, but the name is a trademark for bottled water)

P.S. The tweets cited in the text:

1. By former UK trade official David Henig:

2. By former UK trade minister Greg Hands:

3. My own:

Updates:

July 11, 2023 — adding EU-New Zealand trade agreement on protecting “Feta”

January 13, 2022 — adding court ruling and appeal on protecting “Gruyère” in the US

January 5–10, 2021 — general updating to reflect outcome of EU-UK post-transition deal and UK bilateral agreements; adding link and information on GI View; updating data on names protected in the EU from GI View; details of protection in the EU by trade agreement and clarification/correction on how Swiss names are protected in the EU

December 26, 2020 — adding brief update on the post-Brexit agreement

October 14, 2020 — adding update on UK guide for January 1, 2021

September 11, 2020 — adding link to Norway’s updated replies to the WTO questionnaire

August 29, 2020 — adding update and link to new blog post on post-transition situation

December 18, 2019 — adding references and links to the 2019 report of chair of the WTO talks on a multilateral register

May 7, 2018 — references to Switzerland’s “Le Gruyère” have been corrected to reflect protection in the EU under the 2011 bilateral agreement and to remove the assertion that the name is not protected because it’s not in the DOOR database. (Thanks to Christian Häberli for pointing me to the bilateral agreement and the US certification mark)

September 2, 2018 — substantially updated with the UK’s plans published in July, and reactions

September 26, 2018 — added reference to “mirroring” the EU’s system from the “no deal” paper, the section on the meaning of protection, and links to the draft Withdrawal Agreement and EU position paper; restored missing “waitress” image at the top

November 17, 2018 — added provisions from the November 14 draft Withdrawal Agreement

August 9, 2019 — correcting an error so that TSGs are no longer described as a type of geographical indications, with various edits including the count of names. Thanks to Andrew Chapman via Twitter

CC BY 4.0

● Watercress and chives on bread — silviarita on pixaby CC0

● EU and UK GI logos from respective government website; background photo by Chelsea Pridham on Unsplash CC0

● Cheeseboard — Nastya Sensei on Pexels CC0

● Darjeeling tea montage — black tea leaves, photo by Oleg Guijinsky on Unsplash CC0; Darjeeling tea, first flush 2007 Risheehat Estate, photo by David J Fred CC BY-SA 2.5

● Feta — JJ Harrison CC BY-SA 2.5