By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED MAY 29, 2022 | UPDATED MAY 31, 2022

“They said a US trade deal couldn’t be done. It can. We are doing it.”

That declaration by UK Minister of State for Trade Policy Penny Mordaunt is the headline on a piece she wrote on a partisan website to celebrate signing an agreement with the US state, Indiana.

But is it a “US trade deal”?

- It is not with the “US”, but Indiana — a state with 2% of the US population (at 6 million slightly more than Yorkshire or Scotland), less than 2% of the US economy (GDP), and less than 1% of its area (ranked 38th of the 50 US states)

- The actual “trade” content is minimal, when compared with what governments usually sign in trade agreements

- “Deal” is misleading since this is not the conclusion of anything. It’s a memorandum of understanding (MoU) — or joint statement of intent — on future cooperation and on what future talks will cover. The way it’s presented stretches the meaning of “agreement” a lot.

The phrase “trade deal” is itself a problem.

It can mean anything from a simple import-export sales contract for 500 pencils, to deep integration of trade policy as in the EU Single Market for goods, services, labour and capital, or the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (34 chapters totalling almost 2,000 pages).

But Mordaunt uses “US trade deal” deliberately to create the impression that this is something big, not an 8-page memorandum.

No wonder experts struggled to take the announcement seriously.

“I think this means Hoosiers will have to drive on the left now. Could get a bit chaotic out there!” tweeted trade lawyer Simon Lester.

Continue reading or jump to:

What is an MoU? | What does this one say on trade barriers? | What else does it say? | Oh no! Not Brexit!

See also

“UK, Texas and Other US States Should Proceed Carefully, but Not Abandon, Trade Deals” by law professor David Gantz. He looks more closely at the constitutional situation in the US for states striking agreements with foreign countries, and he accepts the contents of the Indiana memorandum at face value whereas in many cases I’d say we still haven’t seen the proof of the pudding.

What is an MoU?

This is how the UK government explains a memorandum of understanding in general:

“A MOU is not a legally binding document. It is a statement of serious intent — agreed voluntarily by equal partners — of the commitment, resources, and other considerations that each of the parties will bring. It has moral force, but does not create legal obligations.”

The one with Indiana is international. It’s a political agreement, not a treaty under UK law (even though the web page puts it under the heading “international treaty”), and as such does not have to be published or ratified by Parliament.

A parliamentary briefing document lists MoUs among “non-treaty international arrangements” not covered by the 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act (see page 42 here):

“Confidentiality and convenience are probably the main reasons for the Government to use political agreements in preference to treaties. They generally do not need to be published or presented to Parliament, although […] the Foreign Office Treaty Section has kept a copy of MOUs concluded by the UK since 1997.”

In legal terms as well as content, this is obviously not in the same category as a free trade agreement.

And yet, in the UK, the government and its media supporters have proclaimed this as a big achievement — “a milestone in trade relations with the US” — with no attempt to dispel the impression that it is the same as a proper trade agreement. Mordaunt calls it a “US trade deal”.

And in Indiana? Almost total silence.

Two exceptions. One was official: a quote tweet by the Indiana Economic Development Corporation, in turn retweeted by state Governor Eric Holcomb. Other than that, there is no news on the websites of the Indiana government or its Economic Development Corporation, let alone a published text.

The other, the only independent media report, was from Inside Indiana Business. (Unlike in the UK where it was covered by the BBC and several national newspapers.)

Which is strange since the UK could be seen as potentially a huge trading partner. The UK population is 10 times the US state’s, and its economy is about 9 times Indiana’s. Perhaps Indiana values trade with its neighbours more — fellow-US states and the top two of its five largest international trading partners, Canada and Mexico (followed by Japan, China and Germany).

What does this one say on trade barriers?

![]()

3. Removing barriers to trade and investment

a. The Participants will aim to identify, and where they exist, seek to explore solutions to barriers to free and open trade, leveraging policy and consultation mechanisms available.

b. Where appropriate, the Participants commit to considering and pursuing solutions to specific market access barriers, such as government procurement, and supporting regulators and professional bodies interested in pursuing recognition arrangements on professional qualifications.

c. The Participants commit to promoting representative and accessible trade missions with a focus on diversity and inclusion, which look to enhance the profile and networks of minority-owned businesses with focused delegations, joint roundtables and other diverse, targeted events.

d. The Participants will look at deepening commercial interactions, including mutual exchange of business delegations, appropriate sharing of market information as well as other cooperative activities.

Placing the memorandum firmly in the territory of free trade agreements, the British government’s press release says “The MoU creates a framework to remove barriers to trade and investment.”

But Indiana has no power to remove tariffs and other US trade barriers such as food safety standards. This is particularly the case for goods, but also for much of services and other areas of trade. Nor can it negotiate removing British trade barriers. That power is federal, with the US government and Congress in Washington.

The trade barriers that a US state can negotiate are limited to actions such as the recognition of professional qualifications. In fact this is one of the few trade barriers specifically mentioned in the memorandum:

“Where appropriate, the Participants commit to considering and pursuing solutions to specific market access barriers, such as government procurement, and supporting regulators and professional bodies interested in pursuing recognition arrangements on professional qualifications.”

And like the rest of the memorandum, this is not an agreement, not even to recognise each other’s professional qualifications. It’s just a pledge to consider and pursue lowering trade barriers “where appropriate” in the future — a statement of intent.

That includes supporting regulators and professional bodies if and when they embark on recognition arrangements for each other’s qualifications. The actual recognition hasn’t started yet. So much for “paving the way” for professionals to “cross the pond”, as the press release puts it.

This section on “removing barriers to trade and investment” has three more paragraphs.

One is on future work to identify trade barriers (meaning they have not yet been identified) and to “seek to explore solutions”.

The other two are on exchanging trade missions and business delegations and improving commercial interactions. If this counts as removing trade barriers, then these activities must be extraordinarily difficult for the UK and Indiana to arrange.

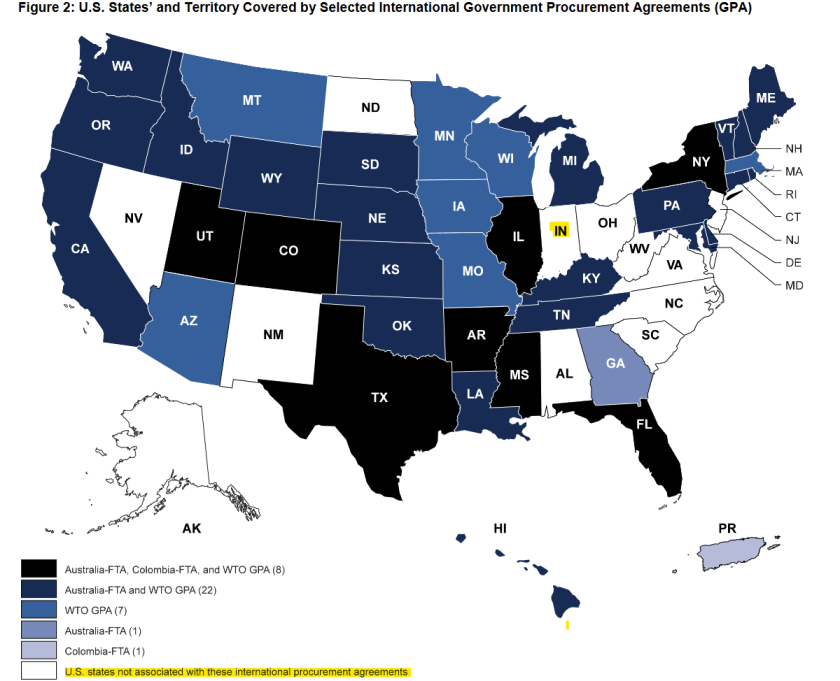

One other area that could potentially tackle real trade barriers is government procurement.

![]()

SECTION 4: GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT

1. The United Kingdom reaffirms its existing obligations under the World Trade Organisation Revised Agreement on Government Procurement (WTO GPA).

2. Indiana will actively work towards offering the United Kingdom’s suppliers treatment no less favourable than that afforded to suppliers from a state not bordering Indiana, including state level preferences.

3. Indiana and the United Kingdom decide to maintain an open dialogue regarding current and future trade related initiatives and developments.

4. The Participants will prioritise and advance opportunities in their government procurement processes within the Working Group framework (outlined below in Section 6).

Here, there is an agreement in the World Trade Organization (WTO), but the situation with the US is complicated because it makes commitments for only some state-level entities, and none in Indiana.

Therefore an agreement to open Indiana’s procurement market to UK suppliers might be useful, although it’s unclear how much access they already have and how much they would gain from a commitment.

The memorandum says that the UK simply reaffirms its commitments on government procurement under the WTO agreement.

Indiana, on the other hand, “will actively work towards offering the United Kingdom’s suppliers treatment no less favourable than that afforded to suppliers from a state not bordering Indiana, including state level preferences,” the memorandum says.

So, not an agreed commitment but a pledge to “actively work towards …”.

![]()

That’s the weirdest MFN clause I’ve ever seen

— Lorand Bartels

The end product would be non-discrimination (most-favoured-nation treatment, MFN). UK suppliers would be able to tender for contracts on the same terms as (“no less favourable than”) suppliers in other US states, including those that have preferences with Indiana except those bordering Indiana — Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio and Michigan. An exception for neighbours is unusual.

“That’s the weirdest MFN clause I’ve ever seen,” says another trade lawyer, Lorand Bartels.

It’s unclear (to me) what “including state level preferences” means. Would the memorandum override Indiana’s “‘Buy Indiana’ presumption” and its preferential procurement policies for US-made products and local coal, steel, agricultural products and other supplies? That seems unlikely.

The rest of the section on procurement is about maintaining “an open dialogue” and “advancing opportunities”.

The memorandum also mentions cooperation on regulations, which can also create trade barriers. But only in a loose sense such as sharing information on “best practices” in regulation, and “cooperation to identify and respond to potential and future disruptions to trade caused by innovation in goods and services” — another promise to talk.

And that’s about it. All in aid of “paving the way for UK and Indianan businesses to invest, export, expand and create jobs” — but within the limitations of what can be done without Washington.

What else does it say?

The rest is mainly collaboration, strengthening ties, exchanging information, exchanging visits, joint research and development projects, “jointly organising symposia, seminars, workshops, exhibitions, and training” … you get the picture.

The areas of cooperation include advanced manufacturing and materials, aerospace and aviation, life sciences, agriculture and agbioscience, automotive (including electric, connected and automated) mobility, low-emissions technology and solutions, and energy and infrastructure.

All very useful, if they happen, and suitable for a memorandum of understanding, but a long way away from a proper trade agreement.

They could have announced cooperation in these areas, and played down the bits about trade barriers and trade deals. We would have applauded quietly, looked forward to actual results, and moved on.

Instead, we get “US trade deal” and the unfathomable inclusion of political buzzwords like “levelling up”.

The memorandum “aims to support our talented professionals with provisions on diversity aligning with our levelling up agenda to ensure economic growth benefits all communities across the country,” the press release says.

“Levelling up.” Does Indiana promise to invest in Teesside? Or to hire lawyers with Brummie accents? Er, no.

This is not the milestone the UK government press release claims. It’s a small step. Let’s call it an inchpebble.

Oh no! Not Brexit!

But — here we go — Minister Mordaunt chose to tweet, “Brexit news: UK scores DOUBLE Brexit trade deal bonus in US and Asia despite Pelosi threat”

Mordaunt was promoting a report in the Daily Express, returning the favour for the paper promoting her big deal with Indiana.

We expect the Daily Express to get things completely wrong.

We shouldn’t expect a minister of state to be so muddle-headed about her own portfolio.

The logic is well-rehearsed.

Brexit removed the UK from the biggest economic integration arrangement in the world: the EU Single Market.

Brexit would allow Britain to make up for this loss by striking trade agreements all around the world. As a participant in EU Common Commercial Policy it could not have done that before Brexit. The biggest prize would now be the deal with the US.

But the one with the US is under threat from politicians, like House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who complain about the UK tearing up an international agreement it signed with the EU — the Northern Ireland Protocol. (Ignore the fact that there are problems in the substance of a potential UK-US deal.)

The crafty British government has found a way round that. It’s gone straight to the states, starting with Indiana.

One small problem. The UK could have signed the Indiana memorandum of understanding as an EU member. I can’t see anything that could have prevented it. Well …

Now, I’m not an expert on the intricate battles over “competence” between the EU and its member states. But as far as I can see, the only bit that the EU might possibly have claimed as its own territory is that strange non-discrimination clause on government procurement.

To be sure about it, I’d need someone who really knows the subject. What I do know is that the EU negotiates government procurement on behalf of its member states in the WTO, but the commitments under the WTO agreement are made by each member state separately as part of the EU package. So I’m prepared to concede that the UK-Indiana MFN clause might not have been possible as an EU member.

But holding workshops? Sharing information? Exchanging trade missions? Encouraging professional bodies to recognise each other’s qualifications? Collaborating on research? Talking to each other?

Give us a break.

Updates: May 31, 2022 — adding the link to news stories from Inside Indiana Business and the BBC, and to David Gantz’s article

Image credits:

Indiana Statehouse | Steven van Elk, Unspalsh licence

Pencils in montage | Kelli Tungay, Unspalsh licence

Map of US states’ participation in government procurement agreements | US Government Accountability Office