By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED JANUARY 13, 2022 | UPDATED JULY 11, 2023

“If you’re new to trade and want to know how to start a brawl between trade people — Simon has the answer.”

That tweet, accompanied by a riotously animated GIF of a bar fight, came from Greg Messenger, associate professor at Bristol University Law School.

“Simon” is another trade law guru, Simon Lester, whose CV includes a stint in the WTO Appellate Body Secretariat.

![]()

Let’s keep up the erosion & make all cheese terms generic!

— Simon Lester

“GI Simon,” punned a third trade law guru Holger Hestermeyer of The Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London.

Lester had tweeted the outcome of a court case as reported on NBC News: “decades of importation, production, and sale of cheese labeled GRUYERE produced outside the Gruyère region of Switzerland and France have eroded the meaning of that term and rendered it generic.”

That quote already contains a lot that is inflammatory in trade. Lester added a couple of gallons (US, of course, 3.785411784 litres each) of gasoline to the flames: “Let’s keep up the erosion & make all cheese terms generic!”

And indeed the comments poured in.

The news was that a US federal judge had rejected an appeal by a consortium of Swiss and French cheese producers after the US authorities refused to register Gruyère as a protected name for a kind of cheese.

The reason? This is what Associated Press (AP) reported (reproduced by NBC News):

“In a decision made public last week, U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis ruled against the Swiss consortium, finding that American consumers do not associate the gruyere name with cheese made specifically from that region. While similar trademark protections have been granted to Roquefort cheese and Cognac brandy, Ellis said the same case can’t be made for gruyere.

“‘It is clear from the record that the term GRUYERE may have in the past referred exclusively to cheese from Switzerland and France,’ Ellis wrote. ‘However, decades of importation, production, and sale of cheese labeled GRUYERE produced outside the Gruyère region of Switzerland and France have eroded the meaning of that term and rendered it generic.’”

Let’s steer clear of the details of US trademark law since I know little about it. (Simon Lester has something to say about that here, as do commentators below the article.)

I do know what World Trade Organization (WTO) rules say about a name like “Gruyère”, which is a “geographical indication (GI)”.

A geographical indication is a name used to define both the origin and the quality, characteristics or reputation of a product.

For cheese, producers have the right to have the name protected if there is a risk that consumers could be confused when producers in other locations use it. That’s what the WTO intellectual property agreement says.

So confusion among consumers is the nub of the issue.

And boy, are Americans confused by the (mis)use of “Gruyère”. (They are not alone.)

Here, absolutely non-legalistically, is an account of the confusion.

Cards on the table. I live in Switzerland. I might exaggerate the “real Gruyère” part a bit.

Continue reading or use the links to jump down the page:

Confusion Exhibits

A: The picture | B: The ‘Gruyère region’ | C: French Gruyère has holes! | D: Comté | E: Swiss Gruyère is protected in the US | F: Swiss Gruyère is not ‘Gruyere’ in the US | G: In the US it’s not a trademark

Footnote

Kiwi contagion

Confusion Exhibit A

THE PICTURE

NBC News produced that picture with the caption “Gruyere has been made to exacting standards in the Swiss region since the early 12th century.”

Whether or not that lump of something can pass as “Gruyère cheese” in the United States of America, it has absolutely nothing to do with the “exacting standards” of the “Swiss region” since yesterday, let alone the early 12th century.

So, please, US friends, remember that SWISS GRUYÈRE DOES NOT HAVE HOLES. It is not a Tom and Jerry cheese. Emmental (or Emmentaler) does.

Confusion Exhibit B

THE ‘GRUYÈRE REGION’

Right at its start, AP’s report spoke of “the Gruyere region of Europe”. Of Europe!

Now, Gruyères (population 2,198) is a tiny medieval fortress town on top of a strategically located hill in Switzerland, plus a small area of surrounding countryside.

It gives its name to the district of Gruyère (population 57,619; area 498 sq km), one of seven districts in the canton of Fribourg.

That’s where Gruyère cheese comes from.

(click or tap the gallery to see the pictures full size)

And yet the people fighting to protect the name Gruyère in the US (for cheese) are a consortium of manufacturers from France as well as Switzerland.

Why? Because those French cheese-makers managed to get their version of Gruyère cheese registered in the European Union as a protected geographical indication or PGI (in 2007) before the Swiss could (in 2014).

To say that the “Gruyère region” extends into France is pushing it a bit.

![]()

It has been produced according to the same traditional recipe since 1115

— Le Gruyère AOP

Actually, a lot. You have to cross at least one other Swiss canton (and in some directions two or three) before you get to the French border.

It’s true that when they started making cheese around Gruyères, Switzerland did not exist. The original three cantons forged their founding alliance in 1291. Fribourg joined the confederation 200 years later. In the meantime, the area was (I think, I’m not a historian either) in a tug of war (with real fighting) between the feudal lords of Bern and Savoie (Savoy, if you prefer).

Apparently Gruyères helped the Swiss rout the Duke of Burgundy’s army shortly before Fribourg joined Switzerland in 1481.

So perhaps the French could claim to have inherited the cheese-making technique through conquest and migration. Which would be ironic since that’s the kind of argument people in the US and Australia make when they rebut French demands for French names be protected in places like the US and Australia.

It turns out that the “Gruyère region” in France is vast, far bigger than the Gruyère-making region in Switzerland. Champagne, the area of the most famous French geographical indication, is in comparison miniscule.

According to the registration document, the zone where French Gruyère can be made stretches from the departments of Haut Marne and Vosges in the north, to Isère in the south, and from Belfort, Doubs and the two Savoies in the east, to Saône-et-Loire in the west. (That’s a crude outline based on the departments named in the document. The eligible areas are defined by sub-divisions of the departments; I haven’t bothered to identify them.)

Confusion Exhibit C

FRENCH GRUYÈRE HAS HOLES!

Remember, a geographical indication defines both the geographical origin and the characteristics of the product.

The characteristics of protected French Gruyère almost fill two pages (US-standard letter size — the full definition covers seven pages). We can ignore it all, except where it says that French Gruyère:

“must have holes ranging in size from that of a pea to a cherry”.

(If you want to see what that looks like, here are some more pictures of cheese with holes.)

So the French and Swiss consortium were pushing for two different types of “Gruyère” to be protected in the US. No wonder the Americans are confused. (Perhaps that NBC News photo was of a French Gruyère. It definitely was not Swiss.)

Confusion Exhibit D

COMTÉ

Personally, I have never knowingly come across or tasted French Gruyère. Nor do I want to.

But I have eaten an excellent French cheese which is as good as Swiss Gruyère. It’s called Comté, described as a “Swiss-type” or “Alpine” cheese, and it is also a protected geographical indication in the EU. Comté is produced in a small part of the area covered by the French Gruyère appellation.

I suspect Comté’s official characteristics do not exactly match those of Swiss Gruyère, but it is very similar. And it does not have holes in it.

This highlights another point of confusion about geographical indications. Comté and Swiss Gruyère might even be identical. That does not matter so long as they do not use the same name.

That’s the only thing that is protected: the name. If “feta” is protected in a country — as it is in all EU members and in Britain — for a type of cheese made in Greece, the same type of cheese from elsewhere such as Denmark, France, the US or Australia can be sold there. It simply has to be called something else, not feta (or Φέτα).

Confusion Exhibit E

SWISS GRUYÈRE IS PROTECTED IN THE US

The court case in the news story was about using the word “Gruyère” alone. However, Swiss Gruyère cheese is protected in Switzerland (and the EU) as a “protected appellation of origin” (in French, “AOP”). The definition runs to 22 pages!

The Swiss Gruyère cheese-makers have now registered “Le Gruyère Switzerland AOC” in the US. “C” stands for “controlled”. AOC is similar to AOP. No one else can call their cheese “Le Gruyère Switzerland AOC” in the US. But they can call it Gruyère, for now at least. Discerning cheese-lovers can find authentic Swiss Gruyère in the US — they just have to look for the label.

(The registration details are here. They can also be found via the US Patent and Trademark Office’s search system, by searching for registration number 4398395 or the name “Le Gruyère Switzerland AOC” or even just “Gruyère”)

In fact, this was secured in the US before Switzerland secured protection for the cheese in the EU.

Confusion Exhibit F

SWISS GRUYÈRE IS NOT ‘GRUYERE’ IN THE US

Which brings us to an important point about geographical indications. What is the definition of Gruyère cheese in the US?

Shock! ‘Le Gruyère Switzerland AOC’ does not meet the official US definition of ‘Gruyere’

The answer is a shock. “Le Gruyère Switzerland AOC” does not meet the official US definition of “Gruyere” (with or without è).

The AOC or AOP labels certify the quality and characteristics of Gruyère cheese, which are at least as important as where it comes from.

But if “Gruyère” is a generic term in the US, can consumers challenge a pretender: “Hey, that’s not Gruyère!”? What’s to stop anyone taking something that’s vaguely cheese, putting it in a fancy package and calling it “genuine Gruyère”?

Geographical indications have owners who can control the quality — the EU calls the branding a “community logo”.

Generic names do not. But the US has a Food and Drug Administration, which does define “Gruyere cheese” in the Code of Federal Regulations.

The US definition is slightly shorter than the French description (if we don’t include the geographical references) and much shorter than the Swiss.

First it says the cheese has a “mild flavour”. That description misses out on the full range of types and affinage (OK, maturity, from 6 to 24 months) that are available. So what chance do Americans have of appreciating a good mature Gruyère?

Then, Gruyère sold in the US can be made with pasteurised milk — Swiss and French Gruyère are strictly non-pasteurised.

Finally, the punchline. The US definition includes this:

“It contains small holes or eyes.”

Sacré bleu !

Confusion Exhibit G

IN THE US IT’S NOT A TRADEMARK

Swiss Gruyère is protected in the US under the trademark system but not as a trademark. Geographical indications are protected in the US as “certification marks”.

If I were uncharitable I might suggest the US deliberately avoids registering geographical indications as such because the whole concept is unpopular there. Remember the oil Simon Lester poured on the flames?

But I am charitable, so I’ll just observe that requiring a geographical indication to be certified is perfectly logical. It is also accepted as a way of meeting the US’s obligations under WTO rules.

Unlike trademarks, geographical indications are not owned by single companies. Any manufacturer, from an industrial-scale cheese factory to a farmer’s small artisanal dairy, can apply to be able to use the appellation of origin — the product is then certified by whichever regional organisation owns the geographical indication, if it meets the conditions (the production area and the product’s characteristics).

Which brings us back to the AP/NBC news story. It speaks of: “similar trademark protections […] granted to Roquefort cheese and Cognac brandy.”

They are not trademark protections. They are protected as certification marks.

That bar brawl is really getting violent. Time to leave.

Footnote: kiwi contagion

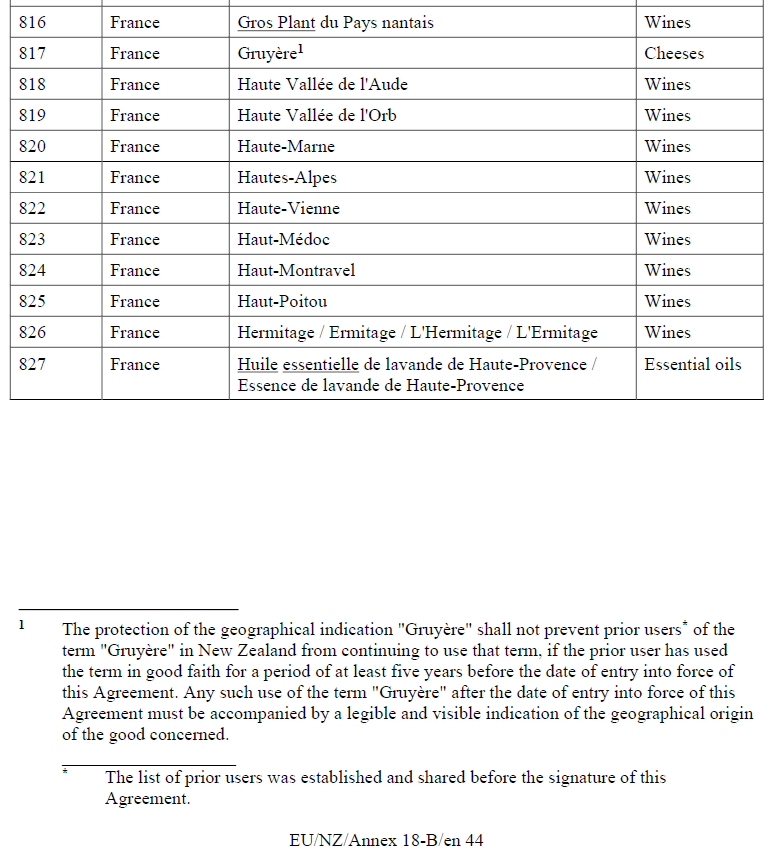

As if that weren’t enough, in its free trade agreement with the EU, New Zealand has agreed (page 781 or EU/NZ/Annex 18-B/en 44) to protect “Gruyère” as a French geographical indication, with the additional proviso:

1 The protection of the geographical indication “Gruyère” shall not prevent prior users* of the term “Gruyère” in New Zealand from continuing to use that term, if the prior user has used the term in good faith for a period of at least five years before the date of entry into force of this Agreement. Any such use of the term “Gruyère” after the date of entry into force of this Agreement must be accompanied by a legible and visible indication of the geographical origin of the good concerned.

A footnote to the footnote adds:

* The list of prior users was established and shared before the signature of this Agreement

But the New Zealand government’s website says:

We are currently establishing a list of prior users for the terms “Gruyère” and “Parmesan”.

July 11, 2023

● More: What are geographical indications? | All posts on geographical indications

● Technical notes: The EU database | Rolling over food and drink names from EU to UK

Updates:

July 11, 2023 — adding “Kiwi contagion” footnote

January 29, 2022 — adding the reference and link to Simon Lester’s post on the International Economic Law and Policy blog

January 20–21, 2022 — expanding on the US definition of (generic) Gruyère with reference to the FDA regulation and splitting it into a separate “exhibit”

January 14–15, 2022 — edits (including separating the section on Comté cheese into a new “exhibit”); adding new links; adding a photo of Gruyères; replacing French PGI and Swiss AOP Gruyère zones map with a more accurate version

Image credits:

Gruyère with holes | NBC

Swiss Gruyère AOP/AOC | Cheeses from Switzerland

Emmental cheese | Coyau, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Gruyères photos | The author, licence CC BY-SA 4.0

Map: background from Google maps.