SEE ALSO

In depth:

Behind the rhetoric: ‘Public stockholding for food security’ in the WTO

WTO fact sheet:

The Bali decision on stockholding for food security in developing countries

All stories on this topic (tagged “food stockholding”)

By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED FEBRUARY 25, 2024 | UPDATED APRIL 22, 2024

It almost wrecked the World Trade Organization’s Ministerial Conference in Bali in 2013. It delayed by a year the final agreement on an entirely separate topic: trade facilitation. It caused agriculture to be dropped completely from the 2022 Ministerial Conference in Geneva, and for the second time in a row, at the 2024 Abu Dhabi conference.

The misleadingly-named “public stockholding” (“PSH”) is currently the most controversial subject in the WTO’s agricultural negotiations.

Those initial letters would more appropriately stand for “(over-the-limit) Price support in food Stock-Holding”.

CONTINUE READING or use these links to JUMP DOWN THE PAGE:

What’s it about? | What are the rules? | What else is demanded? | Who has breached its subsidy limit? | So how’s it going? | In a nutshell

TABLES AND DATA: Which countries have notified eligible programmes? | India’s notified breaches of domestic support limits for rice | Rice, shares of world exports

What’s it about?

It’s probably best to start with what it’s not about.

It’s not about food stockholding. There are no WTO rules against that.

It’s not even about developing countries using subsidies to buy food into stocks, generally.

It’s only about exceeding agreed limits for subsidies used to buy food into stocks. For the countries concerned, those limits are 10% of the value of production (or 8.5% for China).

What’s more, those subsidies are calculated as zero if the food is bought at market prices. We’re only talking about purchases at government-set prices.

For example in 2020/21 India was entitled to subsidise rice purchases into food security stocks by up to $5 billion. Its actual subsidy was calculated at $7.6bn. That’s $2.6bn (52%) more than its agreed limit.

Those are huge amounts. India’s critics accuse it of exploiting its ability to subsidise in this way so that it has become the world’s largest rice exporter. (See data on market shares below.)

What are the rules?

The basic rules in the WTO Agriculture Agreement allow public stockholding for food security with conditions that are slightly more lenient for developing than for developed countries.

In both cases purchases must be at market prices. Developing countries enjoy an exception. They are allowed to buy at government-set prices, but that has to be counted as domestic support. It therefore has to be within developing countries’ agreed limit of 10% of the value of production (8.5% for China).

After a long and sometimes bitter battle, WTO members agreed on a “peace clause” in Bali in 2013. This was delayed a further year after delegations returned to Geneva and India insisted on some changes, or it would refuse to endorse the unrelated Trade Facilitation Agreement.

The result is an “interim” agreement, which remains in place until a “permanent” replacement is agreed.

It says developing countries will not be challenged in WTO dispute settlement (the “peace clause”) when they exceed their agreed domestic support limits when they use price support to buy food into stocks — if they don’t buy at market prices.

The eligible programmes are those that existed at the time of the Bali decision (December 11, 2013) for “staple food crops”.

The few covered include programmes in China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Taiwan, according to a November 2023 WTO Secretariat summary.

This list below from an analysis by a group of WTO members is slightly different.

Which countries have notified eligible programmes?

| Members | Products | Years | Reported in last notification |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Rice, Wheat, Corn | 2014; 2015; 2016 | Yes (2016) |

| India | Rice, Wheat, Coarse Grains and Pulses | 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019 | Yes (2019) |

| Indonesia | Rice | 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018, 2019, 2020 | Yes (2020) |

| Philippines | Rice, Corn | 2014; 2015; 2019, 2020 | Yes (2020) |

| Saudi Arabia | Wheat | 2014; 2015 | No (2017) |

One of the issues in the debate over the permanent solution to replace the interim one, is whether to expand the peace clause to all programmes in all developing countries, or some of them (such as net-food-importing countries).

Governments seeking the shelter of the peace clause have to:

- avoid distorting trade (ie, affecting prices and volumes on world markets) or impacting other countries’ food security

- provide information to show that the limit has been exceeded or risks being exceeded and that they are meeting those conditions

- consult when asked by other countries

India and other developing countries say those conditions are too onerous. They want them relaxed.

Even consultation has been difficult. According to sources, when the issue was discussed in the September 14, 2022 meeting of the regular WTO Agriculture Committee, nine members complained that India had repeatedly dodged their questions.

The nine members — Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Paraguay, Thailand, the US, Uruguay, with the EU saying it might join in — reportedly said India had refused to meet them as a group, insisting on consulting with each individually.

What else is demanded?

![]()

LATEST PROPOSALS (2024)

● The G33, African and African-Caribbean-Pacific groups — May 31, 2022

● Cairns Group (the whole of domestic support) — November 2, 2023

● The G33, African and African-Caribbean-Pacific groups — February 27, 2024

In addition to extending the peace clause to other countries and other staple crops, India and its allies — the G33, African and African-Caribbean-Pacific groups — want to renegotiate:

- How domestic support is calculated — the present formula compares current prices with base-period prices, usually 1986–88. That means inflation and fluctuating exchange rates can give a larger result through the formula. The calculation method is explained here

- The definition of the amount of production eligible for price support in these programmes — one proposal is to use only the amount of produce actually purchased

Other countries — including most of the Cairns Group, the EU and the US — oppose both points.

They say the fixed base periods were deliberately designed so that major subsidisers, particularly in developed countries, could not use inflation as an excuse to increase their entitlements.

They argue that eligible production must remain any part of production that could be bought (ie, available on the market or put up for tender), not the amount actually bought.

And they generally insist that the permanent solution must be part of new disciplines on reducing domestic support as a whole. The US wants to include improved market access in the package as well.

Who has breached its subsidy limit?

Only India. It reported to fellow-members in the WTO Agriculture Committee that in the 2020/21 marketing year, its actual subsidy when stockpiling rices was calculated at $7.6bn. The value of eligible rice production was $50bn, so its entitlement was $5bn. India had exceeded its limit by $2.6bn (52%).

India’s notified breaches of domestic support limits for rice

| Year | Entitlement 10% of value of production | Calculated support (AMS) | Excess |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/2019 | $4.37bn | $5.00bn | $0.63bn (14.4%) |

| 2019/2020 | $4.61bn | $6.42bn | $1.81bn (39.3%) |

| 2020/2021 | $4.56bn | $6.91bn | $2.35bn (51.3%) |

| 2021/2022 | $4.96bn | $7.55bn | $2.59bn (52.2%) |

| 2022/2023 | $5.28bn | $6.39bn | $1.06bn (20.1%) |

As an example of how other countries have responded, in the June 2023 Agriculture Committee meeting, members asked India 15 questions specifically about the subsidies used in food security stockpiling. Other questions on transparency and market price support also related to the programmes. (The questions are on pages 27–37 of this document, the answers are in this database.)

In that meeting Australia, Canada, Paraguay, Thailand, Ukraine and the US presented a “counter-notification” — a notification submitted by other countries instead of the country with a notifiable measure.

In it, they accused India of vastly understating how much market price support it was providing for rice and wheat.

So how’s it going?

Badly. In the WTO agriculture negotiations, members are still deadlocked over these rules. India threatened again to block the 2024 Ministerial Conference if there is no new agreement on over-the-limit price support in stockpiling. And it did just that.

(See, for example, these blog posts from 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. And follow the links back from this page to see how the chair’s drafts evolved in 2021 and 2022.)

On the eve of the Abu Dhabi Ministerial Conference, protesting farmers were reported to be insisting on a new deal at the conference, although their description of how the present rules affect India is inaccurate.

One more point to bear in mind. This is often described as a stand-off between developed and developing countries. In fact there are developing countries on both sides of the debate.

An in-depth examination of the issues is here, including links to further reading at the end: Behind the rhetoric: ‘Public stockholding for food security’ in the WTO

More on the agriculture negotiations

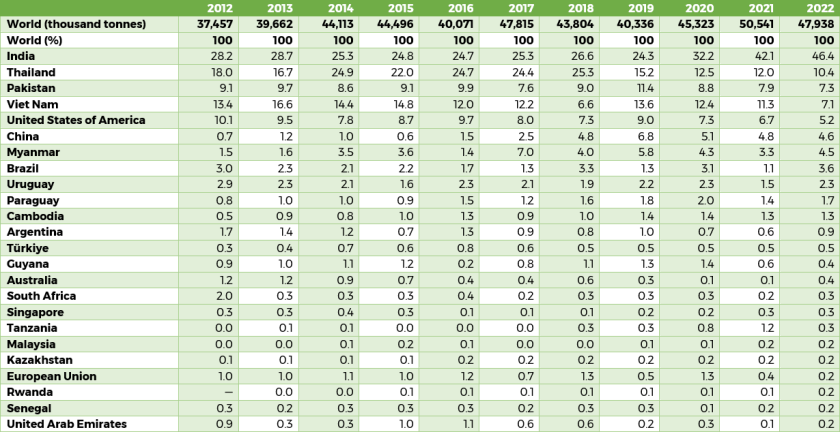

Rice, shares of world exports (%)

In a nutshell

![]()

“PSH”: A MISLEADING NAME

Subsidising purchases into food security stocks is nicknamed “public stockholding for food security in developing countries” or just “public stockholding” (PSH) for short.

The name is misleading because WTO rules do not prevent stockholding. They only discipline subsidised procurement. Even that is allowed, so long as the developing country stays within its subsidy limit, usually 10% of the value of production, which can be a large amount.

This could be described as something like “over-the-limit subsidies used to procure food security stocks”.

The practice is not widespread. A 2022 paper by a Canada-led group found tentatively that since 2013 “only five members notified expenditures […] for stocks acquired at [a supported] price at least once” and only nine since 2001.

Only one country — India — has exceeded its domestic support limit when using subsidies to buy into stocks, and for only one product: rice. For 2021–22, the fourth successive year of the breach, India’s subsidy was calculated at $7.55bn, exceeding its $5.0bn limit by 52%. (The following year the excess subsidy fell back to 20%.)

An “interim” 2013 WTO ministerial decision modified by another decision in 2014 — called a “peace clause” — has protected India from facing a legal challenge despite breaching its WTO commitment.

One problem is that the peace clause is only available to countries with “existing” programmes in December 2013. The few covered include China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Taiwan, according to a November 2023 WTO Secretariat summary.

The present deadlock is over an unresolved permanent solution originally intended to replace the interim one in 2017. Details are here.

(Updated April 22, 2024)

Updates:

April 22, 2024 — adding the 2022/2023 data of India’s subsidies in the table

March 20, 2024 — adding, for clarity, the What’s more paragraph under What’s it about?

March 17, 2024 — adding the table on rice export market shares

March 2 and 14, 2024 — adding the repeat deadlock at the Abu Dhabi Ministerial Conference

Credits:

Rice tricolour | Polina Tankilevitch, Pexels licence