SEE ALSO

Simply put: ‘PSH’, the biggest controversy in the WTO agriculture talks

all stories on this topic (tagged “food stockholding”)

By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED AUGUST 24, 2020 | UPDATED FEBRUARY 10, 2024

In late March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated around the world, India announced it had broken a key trade rule.

It told fellow-members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) that its domestic rice subsidies in 2018/2019 had exceeded the limit it had agreed. But instead of facing a possible legal challenge for breaking a commitment, India invoked a “peace clause” agreed in 2013 and 2014.

The issue is so controversial that the 2013/2014 deal to allow programmes like India’s to escape legal challenge was only possible with a lot of behind-the-scenes arm-twisting and some strict conditions, and only as a temporary fix.

India and its allies were dissatisfied and continued to push in the WTO agriculture negotiations for a permanent replacement with more lenient conditions.

A decade later, members remain deadlocked so badly that agriculture had to be dropped almost completely from the 2022 WTO Ministerial Conference in Geneva — after an odd sequence of events involving India (see below).

It threatens a repeat at the February 26–27, 2024 Ministerial Conference in Abu Dhabi.

![]()

“PSH”: A MISLEADING NAME

Subsidising purchases into food security stocks is nicknamed “public stockholding for food security in developing countries” or just “public stockholding” (PSH) for short.

The name is misleading because WTO rules do not prevent stockholding. They only discipline subsidised procurement. Even that is allowed, so long as the developing country stays within its subsidy limit, usually 10% of the value of production, which can be a large amount.

This could be described as something like “over-the-limit subsidies used to procure food security stocks”.

The practice is not widespread. A 2022 paper by a Canada-led group found tentatively that since 2013 “only five members notified expenditures […] for stocks acquired at [a supported] price at least once” and only nine since 2001.

Only one country — India — has exceeded its domestic support limit when using subsidies to buy into stocks, and for only one product: rice. For 2021–22, the fourth successive year of the breach, India’s subsidy was calculated at $7.55bn, exceeding its $5.0bn limit by 52%. (The following year the excess subsidy fell back to 20%.)

An “interim” 2013 WTO ministerial decision modified by another decision in 2014 — called a “peace clause” — has protected India from facing a legal challenge despite breaching its WTO commitment.

One problem is that the peace clause is only available to countries with “existing” programmes in December 2013. The few covered include China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Taiwan, according to a November 2023 WTO Secretariat summary.

The present deadlock is over an unresolved permanent solution originally intended to replace the interim one in 2017. Details are here.

(Updated April 22, 2024)

At the centre of the debate is food stockpiling in developing countries, officially “public stockholding for food security” (PSH). But the title is misleading. The problem is not stockholding but whether subsidies are used to buy into the stocks. The real issue is a category of farm subsidy, known in the WTO as trade-distorting domestic support for agriculture.

WTO members discussed India’s first breach in the next meeting of the Agriculture Committee in July 2020. Scrutinising potentially controversial measures is one of the committee’s main functions. Some delegations said they wanted to look further into India’s explanations.

India and concerned members remained at loggerheads over how consultations would be organised. In order to avoid legal challenge for the breach, India has to agree to talk. A group of countries wanted to do this together; India insisted on talking to them separately.

![]()

In return for applying the “peace clause”, India has to respond to requests for consultations from members. Sources say that in the Sep 14 meeting, 9 members complained that India had repeatedly dodged their questions.

The 9 members—Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Paraguay, Thailand, US, Uruguay, with the EU saying it might join—said India had refused to meet them as a group, insisting on consulting with each individually, sources say.

— Twitter thread, September 21 2022

India continues to be grilled in detail about the programmes and how transparent it has been. It has now breached its limit in four consecutive years. The amounts are large. For 2021–22 India’s subsidy was calculated at $7.5bn, exceeding its $5.0bn limit by 50%.

In the June 2023 meeting of the Agriculture Committee, members asked India 15 questions specifically about the subsidies used in food security stockpiling. Other questions on transparency and market price support also related to the programmes. (The questions are on pages 27–37 of this document, the answers are in this database.)

In that meeting Australia, Canada, Paraguay, Thailand, Ukraine and the US presented a “counter-notification” — a notification submitted by other countries instead of the country with a notifiable measure. In it, they accused India of vastly understating how much market price support it was providing for rice and wheat.

Meanwhile, in the WTO agriculture negotiations, members are still deadlocked over these rules. (See, for example, these from 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. And follow the links back from this page to see how the chair’s drafts evolved in 2021 and 2022.)

CONTINUE READING or use these links to JUMP DOWN THE PAGE:

What’s the problem? | What are the agreed limits for developing countries?

| How is trade-distorting support calculated? | What has been agreed? |

What are the concerns?

Why didn’t the ‘peace clause’ settle this? | Is a compromise possible? | Developing v developed countries? No | The mysterious revision (2021) | Since 2022

INFORMATION BOXES: “PSH”: a misleading name | Are stocks often bought at government-set prices? | US domestic farm support | Who can support more?

Find out more | Next

The debate has dragged on for years, even though an “interim” solution was found in the 2014 “peace clause”.

It is also characterised by political rhetoric, particularly when WTO trade ministers have met periodically. Some politicians and activists accuse opponents of jeopardising the food security of the poor. But is that really the case? If only it were so simple.

India’s first breach occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic, in marketing year 2018/19 (see the official notification), repeated in 2019/20, 2020/21, and 2021/22 (with some corrections to the data).

The pandemic may have given the discussion a new lease of life. Advocates said this kind of stockholding programme was an essential response to disruptions in agriculture caused by the pandemic and the lockdowns, to avoid food insecurity.

Agricultural production around the world had generally been spared the actual lockdowns, but it was squeezed by disruption in processing and retail, by changes in demand, and by its workers suffering from the disease itself.

In some parts of the world, rural communities saw the mixed blessing of workers returning from the cities, or in some cases a shortage of migrant labour. India saw both.

The United Nations and its Food and Agriculture Organization warned of worsening food insecurity in some parts of the world, although globally food supplies and stocks remained healthy — including in India where “government warehouses are overflowing with 71 million tons of rice and wheat”. The risk tended to be concentrated in some countries.

What’s the problem?

None. Not if governments buy food into the stockpiles at market prices.

In developing countries, the stocks can even be released as free handouts or at low subsidised prices — still no problem. This has always been the case in the 1995 WTO Agriculture Agreement (Annex 2, paragraph 3 and footnote).

Holding stocks of food is obviously necessary for food security, but this particular type of stockpiling programme is by no means the only way.

There are no WTO rules preventing public stockholding for food security

It helps to be clear what WTO rules do and do not say: There are no WTO rules preventing public stockholding for food security.

So what’s the problem, and why won’t it go away?

India and some other developing countries use the stockpiling for an additional purpose — to support farmers and encourage production, which also affects food security.

They buy the produce at prices that are set by the government, not by the market (the official term is “administered prices”).

When they do that, the purchases are counted as “trade-distorting” domestic support for farmers — support that affects market prices and production quantities.

WTO members have agreed limits on this type of support.

![]()

ARE STOCKS OFTEN BOUGHT AT GOVERNMENT-SET PRICES?

The question is important because stocks purchased at market prices are not a problem. It only matters if they are procured at “administered prices” — meaning set by the government.

The answer could be — tentatively — not as often as is claimed. But the information is incomplete, according to a 20-page paper by a Canada-led group. (Updates of the paper can be found here. See also this Twitter/X thread)

A key finding: developing countries’ notifications are incomplete both on their stockholding programmes and when those programmes involve prices support.

The paper says — based on incomplete information — “only five members notified expenditures […] for stocks acquired at an applied administrative price at least once” since 2013 and only nine since 2001. It says more information is needed to assess the proposal properly.

In technical sessions in the WTO, some delegations argued that market prices are difficult to determine because markets are not working properly, so their governments cannot avoid setting the prices.

Whatever the reason, two features now come into play.

One is the agreed limits on the support. The other is the formula for calculating how much support is actually given.

What are the agreed limits for developing countries?

For almost all developing countries, the only limits on trade-distorting domestic support are “de minimis”, conceptually small but in practice potentially large since it’s linked to the value of production.

All developing countries are allowed to up to 10% of the value of production (except China, which has agreed 8.5%).

The limit for developed countries is 5% of the value of production, but several have an additional “AMS” entitlement (see below) because they they started off (in 1995) cutting it from much higher levels.

In practice the limit could be double those amounts. De minimis support can be given for individual products such as rice or beans (“product-specific” support). The 5%, 8.5% and 10% limits apply to the support for each product.

Additional support can also be given to the whole of agriculture (“non-product-specific” support), with those same percentages allowed. Rice and beans can also benefit even if they are not specific targets, meaning they can receive a double dose of de minimis support.

So the ultimate limits are 10% for developed countries, 17% for China and 20% for developing countries.

In a recent notification to the WTO, the US said it provided product-specific support for 95 products, from alfalfa seeds to wheat, 77 of them within the 5% de minimis limits, and 18 exceeding that and therefore subject to a higher “AMS” limit (explained below).

![]()

US DOMESTIC FARM SUPPORT

Consists of de minimis plus AMS above de minimis. For each, the support is for specific products or agriculture more broadly (non-product specific)

DE MINIMIS

Product-specific — Alfalfa seed, almonds, alpacas, apples, apricots, avocados, barley, beans (fresh & processing), beef cattle & calves, bison, blueberries, broccoli, buckwheat, cabbage, camelina, cantaloupe, celery, cherries, chickpeas, chile peppers, corn, cranberries, cucumbers, cultivated wild rice, dairy, deer (in captivity), equine, figs, flowers, goats, grapes/raisins, grasses, green peas, hay and forage, hogs and pigs, honeydew, kiwifruit, lemons/limes, lentils, lettuce, livestock, llamas, macadamia nuts, mint, miscellaneous fruits/nuts/vegetables, melons, and other crops, nectarines, nursery, oats, olives, onions, oranges, orchards/vineyards/nursery, peaches, pears, pecans, peppers, pistachios, popcorn, potatoes, poultry, pumpkins, rice, rye, safflower, sesame, sheep and lambs, soybeans, squash, strawberries, sweet corn, sweet potatoes, tangerines/mandarins/tangelos, taro, tobacco, tomatoes, walnuts, watermelon

Product-specific de minimis = $1.2bn

Non-product-specific = $3.4bn

TOTAL DE MINIMIS = $4.6bn

FULL AMS ABOVE DE MINIMIS

Product-specific — Bananas, canola, coffee, cotton, dry beans, dry peas, flaxseed, grapefruit, honey/apiculture, millet, mustard, papaya, peanuts, plums/prunes, sorghum, sugar, sunflower, wheat.

Product-specific full AMS = $4.3bn

Non-product-specific full AMS = 0

TOTAL FULL AMS = $4.3bn

TOTAL DE MINIMIS + FULL AMS = $8.9bn

(from notification for marketing year 2017 in document G/AG/N/USA/135, 24 July 2020)

Back to India’s limit-breach — it told the WTO that in 2018/19, its trade-distorting support for rice was just over $5 billion. The value of rice production was $43.7bn, so the support exceeded the 10% limit of $4.4bn.

In 2019/20, the support increased to just over $6.3 billion, exceeding the $4.6bn 10% de minimis limit by even more — the value of production was notified at $46.1bn.

How is trade-distorting support calculated?

![]()

WHO CAN SUPPORT MORE?

A crude calculation suggests China’s entitlement could now be more than double the US’s and growing. But China argues that this is less than the US’s when measured per person or per farmer.

China’s entitlement is de minimis, 8.5% of the value of production, but finding the actual de minimis numbers is not straightforward.

China’s latest notification for domestic support is for 2011 (document G/AG/N/CHN/42, December 14, 2018). It values agricultural production (for product specific and non-product-specific support) at about CNY10.73 trillion or roughly $1.7 trillion (2011 exchange rate).

China’s de minimis limit for 2011 would be roughly $141bn. Since then China’s agricultural production will have grown.

For the US it’s both AMS and de minimis.

The US AMS limit is $19.1bn. In marketing year 2017, the US also claimed de minimis (product-specific and non-product-specific) on production worth $864bn (document G/AG/N/USA/135, July 24, 2020). The 5% de minimis limit on that would be $43.2bn. Together with AMS, the effective entitlement for the year would be about $62.3bn

How did India arrive at that $5bn figure? Using a formula in the WTO agreement known as the “aggregate measurement of support (AMS)”, which applies only to trade-distorting support.

AMS is the difference between the present support price and the original 1986–88 reference price multiplied by the quantity of production that is eligible for the support

Countries that had large amounts of support before 1995 were allowed more than de minimis provided they reduced the support — often known as “Amber Box” support, explained here.

The formula may seem odd since the base period is now over 30 years old. But it was designed this way for a reason: to prevent the big subsidisers — the EU, US, Japan, etc — from using inflation as an excuse to reduce the calculated figure for the support (AMS), effectively increasing the entitlement to subsidise.

It would have been updated back in 2008 if members had agreed on the draft deal on agriculture (see page 39), including an overhaul of domestic support calculations. Ironically the 2008 talks broke down over a twin issue — the special safeguard mechanism — also pushed by the same group of countries.

The base period is fixed; the actual current support prices can be affected by inflation, so the gap between them increases with inflation, giving a bigger AMS number.

India and its allies did propose changing the base period for stockholding, but other WTO members were reluctant to tinker with the formula.

Even the concept of “eligible production” is controversial — is it right to say only the quantity actually purchased was “eligible”, or should it be total production?

What has been agreed?

After about a decade of deadlock in the WTO agriculture negotiations, members eventually agreed on the “interim” solution in 2014, which refers to a 2013 WTO ministerial decision.They said that for these programmes, even if domestic support limits were breached, they would not launch a WTO legal dispute — the “peace clause”.

But to alleviate concerns among a number of members that this might impact other countries and world markets, the decision also says countries breaching the limits have to provide additional information and be prepared to discuss the breach with other members (see this fact sheet). India’s notifications for 2018/19 and 2019/20 include the required information.

What are the concerns?

India is the world’s largest rice exporter. It is buying the rice at a subsidised price, holding it in stocks and then releasing it. India has assured WTO members that the released rice is not exported.

But many of them are unconvinced. Even if particular grains of rice are not exported, the release is bound to lower prices on India’s domestic market. And since India is a major exporter, that is bound to lower India’s export prices and affect world markets.

Concerns have been raised, not only by competing exporters such as Thailand, Uruguay and Paraguay, but also others such as Pakistan who have argued that cheaper Indian rice would be imported and hurt their own farmers.

On July 15, 2021 and May 11, 2022, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, the US, Uruguay and Thailand circulated a paper presenting “factual and analytical information” on the issue, focusing on how members have used this type of policy.

They made their purpose clear: to negotiate a permanent solution that “does not lead to distortions or uncertainty in international agriculture markets, and that does not adversely affect the food security of other Members, including developing country Members.”

In late 2023, the Cairns Group (except members that are also in the G–33) circulated a new proposal for cutting domestic support as a whole. Subsidies used for food security stockpiling would be handled within that broader objective, bigger subsidies facing stricter constraints.

Why didn’t the ‘peace clause’ settle this?

India and its allies have argued repeatedly that the obligations on providing information are a bureaucratic burden that is too heavy for developing countries to bear because of limited resources and difficulty in collecting the data.

They were only willing to accept the peace clause and its transparency conditions as an “interim” solution. They continue to push for a permanent one that makes it easier to stockpile food when bought at government-set (“administered”) prices.

Other countries are unconvinced, particularly if the stockpiling country is a major exporter.

Is a compromise possible?

In theory, yes. In theory. In practice it will take significant climb-downs, which seem unlikely (to put it mildly) in the present climate — bearing in mind also that WTO decisions are only by consensus.

In the end it might need emerging economies such as India and China to recognise that there are genuine concerns over the impact on international markets when they are major exporters. This might allow the other countries to accept more flexibility on transparency for smaller players that have genuine capacity constraints.

The price of achieving that recognition might also be agreement by developed countries to cut their entitlements to use trade-distorting domestic support in general. Sometimes trade-offs like this work. But it would add another layer of complication. And, for example, there’s no sign the US would accept it.

Because this issue has become so symbolic, WTO members could waste another decade debating it inconclusively. Meanwhile the peace clause will remain in place.

Developing v developed countries? No

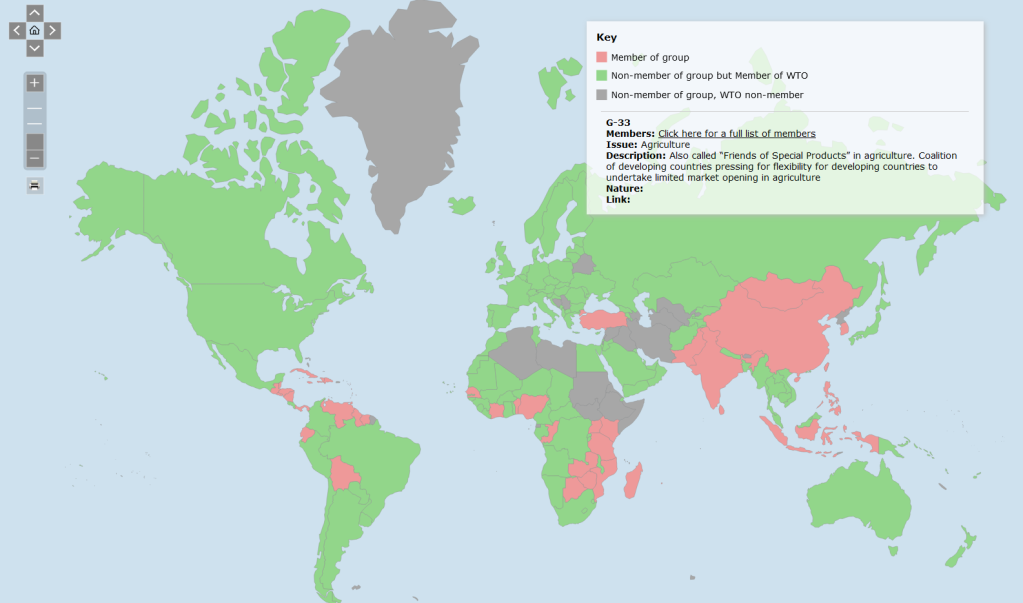

Officially the proposal comes from a group of developing countries known as the G–33, currently 47 WTO members. The group’s official coordinator is Indonesia, which has also been a vocal advocate, as have some other members such as the Philippines.

But India has been the most prominent proponent and it’s the first to have a programme that breaches the de minimis limit and to invoke the peace clause.

The debate is sometimes described as a tussle between developed and developing countries, not least because the most visible confrontations at WTO ministerial meetings have been between the US and India.

But that description is wrong. A number of other developing countries oppose this and other proposals from the G–33, including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Pakistan, Paraguay, Thailand, Uruguay and others.

The mysterious revision (2021)

On July 28, 2021, the G–33 circulated a revised proposal with the aim of persuading the WTO membership to agree to it at the next Ministerial Conference in four months time, scheduled for November 30 to December 3.

This included a provision designed to reassure other countries that the subsidised produce would not have an impact on export markets. The proposal included transparency requirements and this:

5. A developing Member shall endeavour not to export from the procured stocks covered under paragraph 1 of this Annex unless requested by an importing Member.

6. Paragraph 5 shall not apply to exports for the purposes of international food aid, or for non- commercial humanitarian purposes.

India was not included in the list of G–33 members sponsoring this proposal.

“India is not comfortable with providing a commitment about not exporting from the procured stock as it may prove to be a dampner for its farm export drive,” a source tracking the matter told Amiti Sen, who broke the story on September 15, 2021 in The Hindu’s Business Line (paywalled here).

Biswajit Dhar, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University told Sen: “The G–33 anti-circumvention safeguard, stating that a developing country will not export from procured stocks, has put India in a spot as it now exports both wheat and rice and its farm exports are growing.

“Earlier, it used to export only basmati, and hence it could argue that the exports were not from procured stock. Since, for the last couple of years, it has also been exporting non-basmati, the argument doesn’t apply. It is very difficult for it to now prove that exports are not taking place from procured stock.”

Within hours, the G–33 circulated a revision, the only change being the addition of India to its list of sponsors. The full text is here.

Sen’s follow-up (“WTO: India finally accepts G-33 proposal on MSP doles”) was published on September 18, 2021.

Since 2022

Since May 2022, the G–33 (including India), African and African-Caribbean-Pacific groups have argued for a revised version in document JOB/AG/229 (not released publicly).

Meanwhile, in late 2023, the Cairns Group (except members that are also in the G–33) circulated a new proposal for cutting domestic support as a whole. Subsidies used for food security stockpiling would be handled within that broader objective. Bigger subsidies, such as India’s for buying rice into the stocks, would face stricter constraints.

India refused to discuss the Cairns Group’s proposal in a meeting specifically on subsidised stockpiling.

And that summed up the situation as the 2024 Ministerial Conference approached.

The issue has become a stand-off between India and its allies who insist that a permanent set of rules must be a separate decision, and those (Cairns Group members, the US, the EU) who say it must be part of a broader package.

Find out more

- Procuring Food Stocks Under World Trade Organization Farm Subsidy Rules: Finding a permanent solution — Joe Glauber and Tanvi Sinha, International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), August 2021

- On Food Security Stocks, Peace Clauses, and Permanent Solutions After Bali — Eugenio Diaz-Bonilla, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) working paper, June 2014

- Food Security and WTO Domestic Support Disciplines post-Bali — Alan Matthews, International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD), June 2014

Next

Behind the rhetoric: the special safeguard mechanism

More on the agriculture negotiations

Updates:

February 9–10, 2024 — revising adding content to make it more up-to-date, including links to the new draft by the chair and the latest G–33 and Cairns Group proposals, the June 2023 counter-notification, and updated figures on the size of India’s limit breach

October 22, 2023 — adding new links to developments in the negotiations since 2021 and minor modified references to the use of base periods in AMS calculations

September 21, 2022 — adding continuing deadlock in the WTO Agriculture Committee over consultations with India and the link to the Twitter thread

May 23, 2022 — adding the box on “Are stocks often bought at government-set prices?”

September 18, 2021 — adding the new G–33 proposal and India hesitating to join in

July 20, 2021 — adding India’s 2019/20 notifications, the new July 15 paper from six countries, expanding the list of developing countries opposing or sceptical about the proposal

April 10, 2021 — adding India’s 2018/19 notification, and a link to the original Bali decision

September 10, 2020 — adding the “Who can support more?” box

Credits:

Graphics as credited. Photos all royalty-free except where stated.

● Worker with rice sacks | Yogendra Singh, Pexels licence

● Women working in their rice paddy fields in Orissa in India | Justin Kernoghan, Wikimedia, CC 2.0 generic.