This replaces a 2017 article on tariff quotas, originally the second part of a pair of primers on the UK, its WTO membership, and its WTO schedules of commitments. The first part on the UK’s WTO membership is here. The original second part is archived here. See also: Beginner’s guide.

By Peter Ungphakorn

POSTED SEPTEMBER 12, 2018 | UPDATED JUNE 28, 2023

From autumn 2017, news appeared every few months about the UK’s proposed World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments and the objections of other countries. Some claimed this was a failure of London’s Brexit policy.

Headlines spoke of plans “in tatters” or “hitting the buffers”, “protests” by other countries, and even a Kremlin plot. They were wrong, at least for the time being.

Britain left the EU on January 31, 2020. It left the EU’s common commercial policy (particularly the customs union) when the Brexit transition ended on December 31, 2020. In practice, it is now operating under its controversial proposed commitments in the WTO on tariffs, tariff quotas, farm subsidies and access to its services markets.

So the headlines in the public media have gone quiet, and will stay quiet unless other WTO members kick up a fuss. Inside the WTO, those members continue to raise objections in the WTO such as the November 2020 meeting of the Market Access Committee. But it is too soon to tell whether they will take any legal action.

Meanwhile countries had been negotiating quietly and in early 2021 information emerged of agreements between some of them and the post-Brexit EU27, particularly on tariff quotas. The UK stayed quiet but EU sources are quoted saying the UK was part of the talks.

The EU said it was negotiating with 21 countries. By March 2021 it had reached agreement with eight: Argentina, Australia, Cuba, Indonesia, Norway, Pakistan Thailand and the US. As the EU Council gradually approved these, details emerged. The negotiations left some quotas as proposed with no change. Some others were changed. (Details are in “renegotiated post-Brexit tariff quotas”.)

And while all of that was going on, other moves were afoot. The main focus has been, and continues to be on tariff quotas on imports into the EU and UK after the separation. But quotas that used to be for the whole EU pre-Brexit, also have to be split between exports from the UK and the EU27 after Brexit. The US announced how it was doing this on July 6, 2021.

What exactly happened? And what does it mean?

A brief overall view of the UK’s WTO membership and the three main areas of its commitments — goods, services and government procurement — can be found in “what the UK had to negotiate in the WTO”.

The rest of this piece delves into the most difficult topic — tariff quotas — and what has happened on that and the other commitments of the UK and EU on goods imports under WTO procedures.

Continue reading or use these links to jump down the page:

Goods commitments, different approaches?

The UK | The EU

In the WTO

Joint UK-EU approach | Data anomalies | Bigger problem: the approach | Legality, politics and uncertainty | A bit more detail: what happened in October 2018?

Additional technical papers

Renegotiated post-Brexit tariff quotas | What the UK had to negotiate in the WTO | Data and other problems with UK tariff quotas

GOODS COMMITMENTS: DIFFERENT APPROACHES?

Much has been made of the different approaches of the UK and EU, but the reason for the difference is not always understood.

The UK wants to minimise any negotiations it might face in the WTO, and to play down the obstacles. So it stresses that it is “replicating” the commitments it has through the EU. The EU is going directly to negotiations to “modify” its commitments.

That’s not as contradictory as it sounds. The main reason for the difference is that Britain and the EU are doing different things, but for the time being they are doing them together.

The UK

A list of key dates can be found here

THE UK, EU PROPOSALS IN THE WTO

The four papers that the UK and EU circulated in the WTO in July 2018:

- The UK’s covering document and explanation, July24, 2018

- The UK’s proposed goods schedule, July24, 2018

- Data used to calculate the tariff quota splits, July24, 2018

- EU’s proposed tariff quota modification, July24, 2018 (excludes attached — “offset” — data files)

(These leaked documents were obtained by Bryce Baschuk of BNA Bloomberg)

The UK has submitted an entire goods schedule, and to repeat, that covers tariffs, tariff quotas, agricultural subsidies and some other issues such as agricultural safeguards (products marked as eligible for temporary tariff increases to deal with import surges or price falls).

WTO members have queried the UK’s draft on all four points in meetings such as the Market Access Committee in November 2020. The EU has been questioned too.

The British document is 715 pages long. Most of that is likely to be accepted. Only about 25 pages are up for serious negotiation, about 3.5% of the document.

For tariffs, Britain said it would stick to the EU’s tariff commitments, which were its own too, as an EU member, and then until the end of the transition. This also applied to products marked eligible for agricultural safeguards. The UK has kept those commitments.

So if the EU has an 8% maximum tariff for some kinds of shoes, Britain has kept that 8%.

Its original draft schedule literally copied and pasted all the tariffs from the EU’s goods schedule. They cover about 685 pages of the 715.

Even where an EU tariff is expressed in euros (per tonne or whatever quantity), at first Britain made no attempt to convert these into pounds.

At the time, few Brexiters noticed or commented on the fact that the UK’s tariff commitments in the WTO after Brexit are still going to be in an EU currency.

Why? Keeping tariffs in euros means the schedule can be agreed more quickly, without haggling over an appropriate exchange rate.

It would have also been practical if the UK and EU were to have a customs union, at one time a possibility for the post-Brexit relationship.

“Several members also expressed concerns over the UK’s initial rectification of its goods schedule, which was circulated in July. They stressed that the rectification contains substantial changes to the UK’s current WTO concessions, including the UK’s Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS) commitments and Special Agricultural Safeguard (SSG) entitlements, and the proposed methodology to convert the commitments expressed in euros into pounds sterling.

“In its response, the UK referred to the ‘UK Global Tariff’, the long-term applied most-favoured nation (MFN) tariff regime that will take effect from 1 January 2021 following the end of the transition period. This is a bespoke tariff tailored to the UK’s economy expressed in pounds sterling. The UK indicated that the exchange rate at which the new schedule has been redenominated (€1 = 0.83687 GBP) represents the average of the daily exchange rates between 2015 and 2019. It reflects the most recent and relevant economic conditions at the time, ensuring the scope of the concessions and commitments offered for application to the United Kingdom are not altered, the UK said.” — WTO news story, November 16, 2020

The regular tariffs should have faced few objections, but a correction (“rectification”) circulated in July 2020 triggered a number of additional questions in November 2020, including about the conversion of euros to pounds sterling.

Meanwhile, on May 19, 2020, Britain announced a new “UK global tariff”, keeping some applied tariffs at the ceilings committed (or “bound”) in the WTO in order to keep protection for producers, simplifying others, converting those in euros to pounds and cutting a number of others to zero in order to lower costs for producers and supply chains.

Applied tariffs do not need to be notified formally to the WTO, but for transparency members inform each other. The UK did this in the Market Access Committee on June 8, 2020.

Since the applied rates are below the legally bound rates, this is not a problem. But raising the tariffs above the bound ceilings would require renegotiation.

And since the rates expressed in pounds use a conversion rate of about £0.83/€, an appreciation of the pound might be a problem unless the UK converts these new tariffs into WTO bindings.

The new rates, applying from the end of the withdrawal transition are here (pdf) and here (Excel).

To establish UK-only ceilings on agricultural subsidies only two numbers are needed. One of them has some problems, but they are theoretical rather than practical, for the foreseeable future.

One number is a simple zero. Both the UK and EU committed to scrapping export subsidies. This is uncontroversial because it’s a WTO deal from 2015 they all agreed to.

The other is the domestic support entitlement. Here the committed ceiling across the EU is much higher than the actual support given to farmers — we are talking about “trade-distorting” support which has a direct impact on prices and production, not broader support that is not linked to them.

There are no signs that Britain will suddenly become the world champion trade-distorting agricultural subsidiser, which would be totally out of character. Therefore, the discussion with other WTO members, about how much of that ceiling should be given to the UK, is largely to ensure that the calculation is technically and legally acceptable. It’s unlikely to be about political or commercial interest.

The UK has proposed a trade-distorting support limit of €5,914.1 million (basing the calculation on the original entitlement for the EU12 that negotiated the limit in the 1980s and 90s). It’s this method that other members are still querying in WTO meetings, perhaps more for the legal precedent of the method used rather than the actual outcome.

Since then, the UK has converted its proposed commitments to pounds. For trade-distorting support the claimed limit is £4.95 billion. In 2022, the UK said it only used £9.62 million (less than 0.2% of the entitlement).

For comparison, the EU’s limit is €72.4 billion. Its actual support is currently about €6 billion.

Some WTO members have challenged the method the UK used to arrive at its domestic support limit.

That leaves 100 or so tariff quotas (the EU counts 124 on agricultural products and 18 on others). And here, the UK admitted it was likely to have to negotiate with other WTO members. They are on 25 pages out of the 715-page document.

On June 12, 2018, Greg Hands, at that time a minister in the International Trade Department, wrote to the chair of the House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee:

“Should it be necessary, the UK may then move on to a second stage, and open our own […] negotiations, on a UK-specific goods schedule and tightly constrained to residual specific tariff rate quota lines where rectification with our partners has not been finalised.”

The nuances might be different, but in practice that’s what the EU is doing too.

Together, the UK and EU clearly intended to apply the tariff quotas unilaterally after the end of the transition, from December 31, 2020 even without agreement in the WTO.

Then as the Brexit transition ended on December 31, 2020, UK announced the tariff quotas it was applying in 2021. The announcement is not easy to understand, not least because it contained no descriptions of the products, only customs code numbers (see the original in Word and pdf formats).

Thanks to slroot@schnoogsl and Jim Cornelius @Jim_Cornelius on Twitter, we now have product descriptions too. Here’s slroot’s original work in Excel format, tweaked further to split into three parts according to allocation method in Excel, pdf and Word formats.

And on January 19, 2021 the UK told the WTO membership what the 2021 tariff quotas are. The notification to the WTO Agriculture Committee is much easier to follow because it includes product descriptions and other details — as required for transparency in the committee’s 1995 decision on notifications.

The EU

For its part, Brussels only submitted revised tariff quotas. It does not have to touch its WTO commitments on tariffs — the UK’s departure has no effect on them.

It does not have to reduce its entitlement to support farm prices and incomes, although other WTO members might not agree — they could demand a lower entitlement since the EU would be smaller.

The EU’s document is only 16 pages of tariff quotas (excluding accompanying data).

In 2021, the EU published its own updated information on tariff quotas here, including how the post-Brexit quotas were calculated.

The British and EU approaches look different. But on the key question of tariff quotas they are not, and they are actually closely linked.

IN THE WTO

A list of key dates can be found here

Joint UK-EU approach

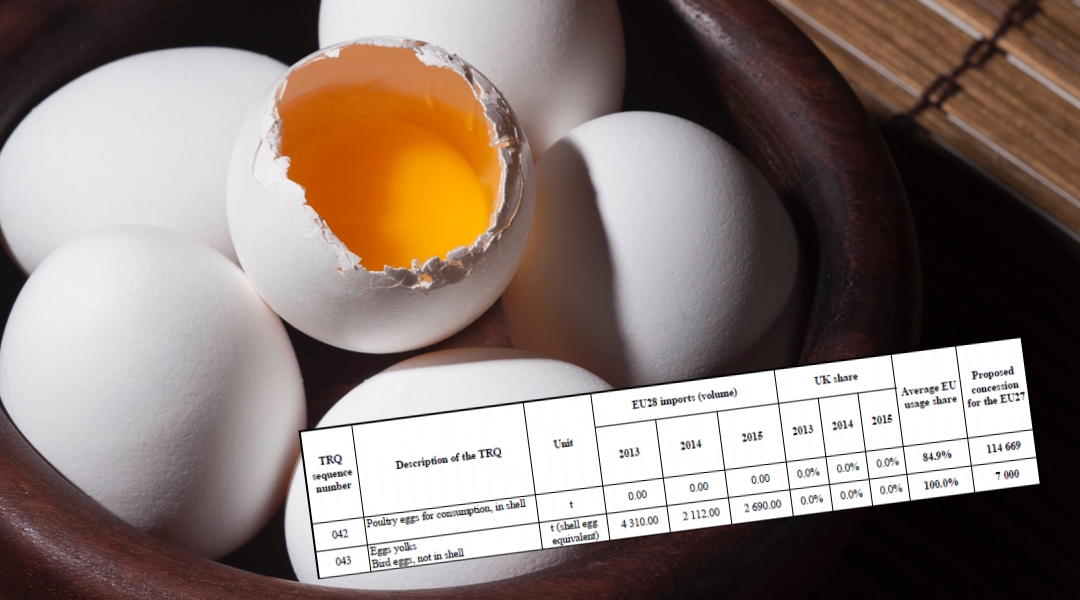

From the start, Britain and the EU announced a joint approach on tariff quotas. They would split the present quotas for the EU28 according to the proportions of imports going to the UK and to the EU within those quotas.

A crucial principle was that each EU27 and UK quota for any product would add up to the original EU28 quota for that product:

EU27 + UK = EU28

The joint approach was announced in a letter from the British and EU ambassadors to their WTO counterparts, published on October 11, 2017.

They then clarified that the basic split would be “based on the average imports to the UK and EU27 within the quota during the representative period of 2013 to 2015” — the three years immediately before the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016.

For example:

The EU28 tariff quota for butter from New Zealand was:

74,693 tonnes per year.

According to EU data:

63.2% of imports through the quota ended up in the EU27

36.8% went to the UK.

Those percentages were used to split the quota. So the quota

in the proposed UK schedule is 27,516 tonnes

and the revised number

in the EU27’s schedule is 47,177 tonnes.

The sum of those two numbers is:

the original 74,693 tonnes.

The fact that the UK and EU27 quotas add up to the original EU28 quota complies with the principle the two announced from the start.

The EU agreed to negotiate from the start because it was modifying its commitment (the WTO procedures are explained in “data and other problems with UK tariff quotas”).

So if it negotiates with New Zealand and ends up with a different figure, the UK’s quota would automatically change too, unless the joint approach is dropped. The UK would almost certainly want to be part of that negotiation.

Hypothetically, it’s possible that New Zealand and the EU agree to a 50,000-tonne quota for the EU27.

Under the joint approach, that would imply cutting the UK share to 24,693 tonnes. The UK would have no problem with that. It can always apply a larger tariff-quota than its commitment in the WTO.

But New Zealand might insist the UK’s commitment should be no smaller than 27,516 tonnes.

If the UK accepts that, the two quotas would add up to more than the original for the EU28.

Data anomalies

There are a number of problems with this approach.

The first is data. It is difficult to compile, not available publicly and produces some zeros, meaning some tariff quotas are not available to some countries.

This is discussed in more detail in “data and other problems with UK tariff quotas”.

What happened in October 2018?

Suddenly on October 9 and 25 (2018), the media woke up, with those stories of plans “hitting the buffers” and “in tatters”, “protests” by other countries, and even a Kremlin plot.

Because of their sporadic interest, they did not know that what really happened was already expected. After all, the reservations were first raised a year before that, and in June 2018 the UK had conceded that negotiations were on the cards.

What happened since then simply followed a well-trodden WTO procedural path under Article 28 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), only slightly magnified by the special case of Brexit.

It is described in detail in “data and other problems with UK tariff quotas”.

Bigger problem: the approach

A list of key dates can be found here

All of this suggested a lot of talking would be needed before the schedules are certified.

Even before the joint UK-EU letter was circulated to WTO members, a number of countries got wind of the plan and responded with their own letter opposing the joint approach.

Argentina, Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Thailand, the US, and Uruguay wrote to the UK and EU ambassadors in Geneva:

“We are aware of media reports suggesting the possibility of a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union 27 countries about splitting Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) based on historical averages. We would like to record that such an outcome would not be consistent with the principle of leaving other World Trade Organization Members no worse off, nor fully honour the existing access commitment. We cannot accept such an agreement.”

Briefly their argument was that the straight split would decrease the value of their present access to the EU28 market. Before Brexit they could choose to export to Britain, or Sweden, or Greece, or Germany, wherever the price is better and the deal more profitable at any particular moment.

Once the tariff quotas are split, that flexibility is lost and they may not be able to make the most profitable deal.

A number of possible solutions have been suggested. One is for the UK and EU to continue to use single quotas for the EU28 even after Brexit. This would be automatic if the UK was in a customs union with the EU (and that is what happened in the post-Brexit transition period). Or it could be through a customs agreement between the EU and EU specifically to have joint quotas (not on the cards at the moment).

The most obvious alternative would be for the UK and EU27 quotas to end up larger than proposed to compensate for the loss of flexibility.

(From May to July 2018, the EU invited public comment on its proposed revised tariff-quotas. The comments came from 21 countries and organisations, some for, many against the proposal. Comments from Australia and Paraguay were similar to those from the letter writers. The US was silent. The comments can be seen here, and a quickly-compiled summary is here.)

Legality, politics and uncertainty

What if the UK and EU stick to their guns and go ahead with their proposed quotas, as they have done now? What does WTO law say?

The standard answer in an issue like this is: “we don’t know because there has never been a legal dispute on this point in the WTO.” That doesn’t stop speculation.

Some lawyers argue that provided the calculations have been made carefully, the UK and EU would win any legal challenge in the WTO because commitments on quotas are about quantities, not the commercial value of access to a market.

Some others are not so sure, and New Zealand and its allies continue to argue that it’s the value of the access that is key. They will push their claim as far as they can. Originally there was no hurry because Britain stayed in the EU customs union during the transition, delaying the need for the tariff and tariff quota parts of the goods schedule. The transition is now over.

Depending on their mood, WTO members can also be practical. The EU has been able to trade for years even though its certified schedules are not up-to-date.

And complaints don’t always end up as legal challenges. From 2010 to 2013 Costa Rica was questioned in every meeting of the WTO Agriculture Committee because it subsidised its rice farmers by up to six times its agreed limit. But this never became a formal dispute because Costa Rica owned up first, and other members were confident it would do what was necessary, including to amend its constitution.

The key was the belief that Costa Rica was acting in good faith.

All of which means the UK and EU could trade smoothly with the rest of the world after Brexit even if the schedules are not certified, provided good faith is preserved.

But if other countries are dissatisfied enough, particularly with the tariff quotas, then they might kick up a fuss and even go to WTO dispute settlement. This will take some time to resolve but it will create uncertainty in trade and sour the mood among countries Britain is targeting for free trade deals.

For now Britain (and presumably the EU) is working hard to preserve the goodwill of other WTO members. How successful it will be remains to be seen.

(See also this explainer by Dmitry Grozoubinski, and his more detailed update.)

PS

QUESTION: There is one other aspect of tariff quotas that is missing from the above, but could have proved crucial for Brexit. Any idea what it is?

ANSWER: The UK and EU have no guaranteed access to each other’s tariff quotas as committed in the WTO. This is no longer an issue now that the 2020 Christmas Eve agreement between the two is completely duty free, which by definition means there cannot be tariff quotas either.

See also

- With little fanfare, the US splits its tariff quotas for UK and EU exports (2021)

- UK, EU, WTO, Brexit primer — WTO membership (2017)

- A real beginners’ guide to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) and the WTO (2018)

- Comments on the EU’s (and UK’s) proposed modified tariff quotas (2018)

- Archived: UK, EU, WTO, Brexit primer — 2. Tariff quotas (2017)

- The limits of ‘possibility’: Splitting the lamb-mutton quota for the UK (2017)

- The Hilton beef quota: a taste of what post-Brexit UK faces in the WTO (2016)

NOTE: Parts of this article draw on material researched and written for IEG Policy (now IHS Markit Food and Agricultural Policy), including interviews with a range of WTO delegates. More details are in articles available to subscribers, including:

- UK to circulate draft post-Brexit WTO commitments ‘next year’ — September 25.2017

- Brexit: New Zealand official confirms approach to WTO TRQ talks — October 3, 2017

- EU hands WTO updated goods commitments, includes scrapping farm export subsidies — October 9, 2017

- UK and EU release joint letter to WTO members on approach to commitments — October 11, 2017

- EU joins UK in post-Brexit WTO talks as data emerges as first major hurdle — October 23, 2017

- Analysis: Commission draft raises prospect of no WTO quota deal by Brexit Day — May 23, 2018

- Hard talking on UK and EU WTO tariff quotas finally about to start — June 28, 2018

- WTO members pile into UK-EU proposal for splitting tariff quotas after Brexit — October 9, 2018

- Extending the Brexit ‘transition’ has a by-product: more time to sort out tariff quotas — October 18, 2018

- New services drafts edge the UK towards establishing its post-Brexit WTO position — December 10, 2018

And this one by Adam Sharpe (originally available free-to-view): UK to enter into negotiations with WTO partners on Goods Schedule after TRQ objections — October 25, 2018

Updates:

• June 28, 2023 — adding the UK’s conversion of domestic support limit to pounds sterling

• August 21, 2021 — adding link to updated EU page on tariff quotas

• July 15, 2021 — adding US splits on imports from the UK and EU

• March 25, 2021 — moving to new technical notes: completed negotiations, summary of talks on goods, services and government procurement

• March 11–25, 2021 — adding a major updates on EU agreements with concerned countries, adding the herring quota with Norway, and the extended deadline for negotiations

• January 16–20, 2021 — adding UK confirmation of its applied tariff quotas, files of these with product descriptions added (improved on January 20), links and descriptions of discussion in the WTO Market Access Committee; technical detail moved to new technical note

• November 18, 2020 — adding for clarity that the quota splits are normally based on 2013–15 imports to the UK and EU27

• May 19, 2020 — adding the new “UK Global Tariff” of post-transition applied rates

• December 21, 2018 — adding UK formally launching GATT Art.28 process in the WTO.

• December 14, 2018 — adding agreement in principle on government procurement on November 27, and the circulation of services schedules on December 3.

• October 27, 2018 — adding developments in October 2018, updating the timeline, adding the number of pages of the UK’s and EU’s proposed documents, adding a link to Dmitry Grozoubinski’s explainer (a link to his updated added January 4, 2019)

• September 14, 2018 — clarifying the method used to calculate UK and EU shares of tariff quotas where there have been no imports

• September 13, 2018 — corrected to include justification for the UK’s proposed tariff commitments to be in euros, and adding Reuters report on services schedules being circulated in February; adding figures for UK and EU domestic agricultural support

Photo credits:

• Thun, Switzerland, bridge and weir. Just like a tariff quota, different volumes flow over the high and low parts of the barrier. Photo: Peter Ungphakorn CC SA-BY 4.0

• Other images public domain (CC0)