SEE ALSO

WTO ministers’ meeting — no interaction, no movement, just speeches

Texts: state of play in WTO farm talks and the crisis-meeting invitation

and all stories on this topic (tagged “food stockholding”)

Posted by Peter Ungphakorn

JANUARY 17, 2024 | UPDATED JANUARY 18, 2024

The US, EU and the majority of the Cairns Group told fellow agriculture negotiators at the World Trade Organization yesterday (January 16) that a stand-alone decision on relaxing rules on food security stocks procured with higher than permitted subsidies will not be possible at next month’s WTO Ministerial Conference.

The writing had been on the wall for some time. In this meeting, according to sources, the US seems to have taken the lead, in declaring that deep divisions among members cannot be resolved and therefore a consensus decision at the Abu Dhabi conference will be impossible.

The US reaction is said to have come after India sought to “refresh members’ memory” by recalling mandates from previous years.

The purpose for India and its allies would be to find a permanent solution to replace the present temporary fix for when developing countries exceed their domestic support entitlements through purchases into food security stocks at subsidised prices.

Previously the US had been a lower-key opponent, leaving others, particularly Cairns Group members to lead in arguing that settling this issue must be part of a package for cutting all types of domestic farm support entitlements. (Ukraine has now added its name to the proposal’s sponsors.)

Only 14 of the Cairns Group’s members are sponsoring the proposal — Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Malaysia, New Zealand, Paraguay, Peru, Thailand, Uruguay and Vietnam.

Four other members — Guatemala, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines — are also in the G33 group, which takes an opposing view on this issue. A fifth, South Africa, increasingly aligns itself with India, a driving force behind the G33 position.

In yesterday’s meeting the EU is said to have agreed that subsidised food security procurement must be part of reform of domestic support as a whole.

![]()

“PSH”: A MISLEADING NAME

Subsidising purchases into food security stocks is nicknamed “public stockholding for food security in developing countries” or just “public stockholding” (PSH) for short.

The name is misleading because WTO rules do not prevent stockholding. They only discipline subsidised procurement. Even that is allowed, so long as the developing country stays within its subsidy limit, usually 10% of the value of production, which can be a large amount.

This could be described as something like “over-the-limit subsidies used to procure food security stocks”.

The practice is not widespread. A 2022 paper by a Canada-led group found tentatively that since 2013 “only five members notified expenditures […] for stocks acquired at [a supported] price at least once” and only nine since 2001.

Only one country — India — has exceeded its domestic support limit when using subsidies to buy into stocks, and for only one product: rice. For 2021–22, the fourth successive year of the breach, India’s subsidy was calculated at $7.55bn, exceeding its $5.0bn limit by 52%. (The following year the excess subsidy fell back to 20%.)

An “interim” 2013 WTO ministerial decision modified by another decision in 2014 — called a “peace clause” — has protected India from facing a legal challenge despite breaching its WTO commitment.

One problem is that the peace clause is only available to countries with “existing” programmes in December 2013. The few covered include China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Taiwan, according to a November 2023 WTO Secretariat summary.

The present deadlock is over an unresolved permanent solution originally intended to replace the interim one in 2017. Details are here.

(Updated April 22, 2024)

Mandates

India’s presentation for recalling the mandates echoes its intervention when ministers met on November 28. Despite ground rules limiting speakers to three minutes each, India is said to have insisted in making a 20-minute presentation at the start of that meeting.

And in the agriculture negotiations the week before, India had refused to discuss the Cairns Group’s proposal under the “public stockholding” heading even though the group said their proposal covered the subject.

According to sources, yesterday India said the issue of subsidised procurement for stockholding “has to be dealt with separately on a fast track without linkages, as per the existing mandates”. India insisted that the solution must be delivered at the Ministerial Conference.

India and its allies — the G33, African and African-Caribbean-Pacific groups — want the present temporary solution to be expanded to cover all developing countries, all staple foods and all existing and future programmes.

At the moment, it only applies to programmes that existed at the time of the original decision (December 7, 2013, confirmed in a new decision in 2014). Therefore only countries that had those programmes at the time are eligible, and only for those programmes that existed on that date.

Proponents are also calling for less stringent conditions.

Conditions

The present temporary decision is a “peace clause” shielding developing countries from a legal challenge in WTO dispute settlement if the subsidies in these programmes exceed their agreed entitlements.

In return they have to notify relevant information and be prepared to discuss with concerned countries the impact of the subsidies on other markets. Proponents consider this to be too stringent.

India is the only country so far to have exceeded its entitlement through this type of programme.

Its subsidy for procuring rice at above market prices was calculated at $6.3 billion for 2019–20. This was $2.3bn higher than the $4.6bn support limit it has agreed in the WTO.

India and its allies are also challenging the way the subsidies are calculated.

The proponents’ latest demands are in a document from May 2022, which the sponsoring countries have not released to the public.

The US, EU and Cairns Group are said to have argued in the January 16 meeting that the scale of the subsidies have allowed India to become the world’s largest rice exporter.

The US said the experience of the past decade shows that the present solution has not worked and has been detrimental, according to sources.

The US’s proposal on this issue was for ministers to agree that those pushing for a permanent stand-alone solution should provide data to support their position.

According to sources, speakers in the session included: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chad, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, EU, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Paraguay, Philippines, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, UK, US, Türkiye and Uruguay.

The rest of agriculture

The meeting continued on other subjects including the three “pillars” of agriculture in the WTO (market access, domestic support and export subsidies).

Negotiators also returned briefly to another subject that the G33 group and its allies want settled as a stand-alone decision: the special safeguard mechanism (explained here).

The African Group (Nigeria speaking) called for a ministerial decision next month setting the next Ministerial Conference as the deadline for reaching agreement.

Paraguay, a Cairns Group member, repeated an argument it has been making for years: that this safeguard has to be part of a deal on market access as a whole. Paraguay has long argued that the ability to use safeguard measures of any kind is reassurance for commitments to open markets.

The chair is said to have urged delegations to be more creative and practical on possible outcomes at the Ministerial Conference.

Meanwhile, the African Group has circulated a new proposal on least-developed and net-food-importing developing countries for the Ministerial Conference.

It would help those countries promote production of food that they currently import in significant amounts. It would also increase disciplines on their suppliers’ export restraints. The reaction is said to have been mixed.

Updates:

January 18, 2024 — minor corrections and additions on issues, including identifying the new proposal as coming from the African Group rather than LDCs and net-food-importing developing countries themselves

Image credits:

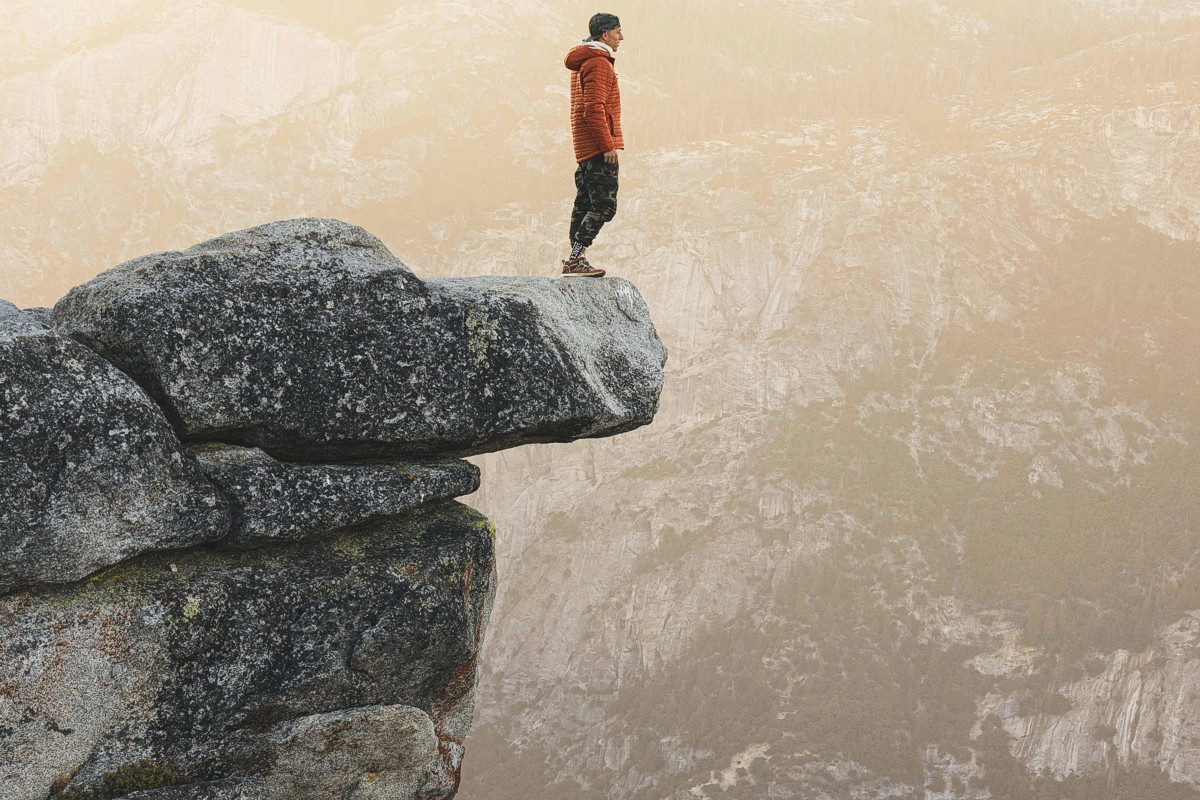

Chasm (main picture) | Stephen Leonardi, Pexels licence

Impossible | Max Bohme, Unsplash licence